The pearl of the Indian ocean has been brewing in its primordial waters: known to ancient Egyptian and Greek worlds, source of all their cinnamon, the shadowy island home of the vilified genius Ravana from the Indian epic Ramayana. Its geography and biodiversity have made it a vortex of trade, travel, pilgrimage and empire. These cultural, biotic and abiotic aspects have acted as selective pressures influencing the cultural destiny of the island and shaping the expression, hopes and habits of its ethnically diverse population.

Sri Lanka’s musical culture has been fruitful and diverse, subject to a variety of influences over the centuries and serving multiple functions from astrological and occult ritual music to harvest song and drinking ballads.

Sri Lanka's proximity to India has led to the adoption of many Indian musical traditions, such as classical Indian instruments and vocal styles. Additionally, the island's strategic coastal location has facilitated the spread of maritime trade, and this has also contributed to the exchange of musical ideas and traditions with other regions.

The country has a long history of colonization, first by the Portuguese in the 16th century, followed by the Dutch in the 17th century, and finally by the British in the 19th century. It has had a significant yet ambivalent impact on the country's musical milieu, as European traditions and instruments were introduced and integrated into the local musical styles.

A relatively unacknowledged but palpable presence in the contemporary popular music of Sri Lanka is its African influence via its small native demographic of Afro-Sri Lankans. These communities have their own unique musical traditions, which have been influenced by both African, European and Sri Lankan musical styles. Today, there are several small communities of African-descended people living in Sri Lanka, the largest of whom refer to themselves as Kaffirs also known as the Sri Lankan Kaffirs.

Presence

Although the presence of Africans in Sri Lanka has been documented as far back as the 6th century, when Ethiopian traders were known to have stopped by the island, the origins of the Kaffirs in Sri Lanka can be traced back to the 16th century, when the Portuguese began importing Africans to the island to work on Portuguese-owned plantations as slaves. Many of these people were brought from Portuguese colonies in East Africa, such as Mozambique and Tanzania.

The Sri Lankan Kaffirs are very similar to the Zanj-descended populations in Iraq and Kuwait, and are known in Pakistan as Sheedis and in India as Siddis. They spoke a distinctive Creole based on Portuguese, which evolved to the almost extinct Sri Lankan Kaffir language.

During the Dutch and British colonial periods, the Kaffirs continued to be brought to Sri Lanka as slaves, but they were also used as soldiers to fight against Sinhala Kings and sailors in the Dutch and British armies. In addition, some Kaffirs were brought to the island as part of the British East India Company's labor force.

When Dutch colonialists arrived around 1650, the Kaffirs worked on cinnamon plantations along the southern coast whilst some had settled in the Kandyan kingdom. Some research suggests that Kaffirs were employed as soldiers to fight against Sri Lankan kings, most likely in the Sinhalese-Portuguese War. Having been domiciled in Sri Lanka earlier, the Kaffirs are distinct from the Portuguese Burghers (Sri Lankans with partial Portuguese ancestry). But the Kaffir and the Burghers in the north-east do share language and culture and there has been exchange / intermingling between the communities, albeit poorly documented.

Present day Kaffirs have been assimilated across the country, intermarrying with the local Tamil and Sinhalese population, and three distinct communities in Trincomalee, Negombo and Puttalam still remain. The majority of around 200 families live in the village of Sirambiayadiya, Puttalam.

While the presence of Afro-Sri Lankans is not well documented and has been perceived as marginal, the cultural impact they have had in the island especially via music is marked and undeniable.

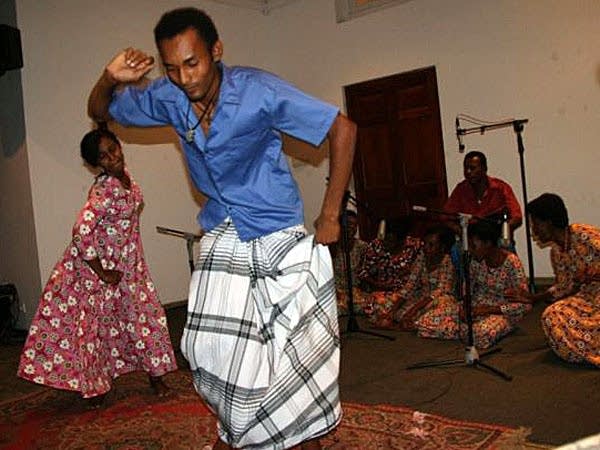

Some of the key features of Afro-Sri Lankan music are distinctly African in its use of polyrhythms, call and response and vocal harmonies. Using these techniques to create intricate rhythms and a lively and interactive atmosphere, the singers would often improvise melodies and lyrics, creating a unique and spontaneous sound.

Influence

The presence of Afro-Sri Lankan culture in the country’s contemporary music scene is primarily felt through the lasting influence of the Kaffrinha (Kaffir + ‘nha’ (which is the Portuguese diminutive)) which is associated with the Kaffirs and the Portuguese; it is sometimes called Kaffrinha Baila (the Portuguese word for dance), suggesting that the music was a Portuguese take on African music played on the island. Kaffrinha in contemporary Sri Lanka is not simply an Afro-Portuguese blend. It is the fusion of three cultures: African, Portuguese and Sinhalese.

The music is played with percussion and string instruments: violins, mandolins, banjos and guitars. It’s always in 6/8 time, with a very syncopated, three-against-two beat, another suggestion of its roots in African music. Notably apart from the Sinhala language, it seems to be lacking in explicit traits from South Asia: the harmonies and melodies tend to be based around the Western major scale.

The writer R. L. Brohier described the music in a Puttalam village called Sellan Kandel, as Kaffrinha and Chikothi. He wrote in the 20th century that the ‘Kaffir-Portuguese Chikothi’ music had been absorbed into Sri Lankan popular culture, surfacing at gatherings which sought an outlet for hilarity – these were given the heterogeneous term Baila. Although in more recent times, Kaffrinha is often associated with the Portuguese Burgher communities, who continue to live on the coasts of the island.

The kaffrinha song, “Meegalu Maalu'' by the Sri Lankans, was recorded in 1978, so it’s probably not what the music would have sounded like in the 1800s, but it gives us at least a vague approximation.

Kaffrinha is also associated with ‘chorus baila’ (most often simply referred to as Baila), a genre of music that blossomed in postcoloniality. The fountainhead of chorus baila, Mervin Ollington Bastianz, was inspired by kaffrinha and ‘vaada’ baila (debate songs or challenge songs were a popular form of entertainment in Sri Lanka, similar to ‘canto ao desafio in Portugal and Brazil) of which he was the superstar. Unsurprisingly, the rhythms associated with African music were thereby absorbed into chorus baila, perhaps the most cherished form of pop music in the country.

The simplicity of Bastianz’s narratives and the realities that he addressed, sizzling and simmering over catchy and memorable rhythms, popularized Bailas. Bastianz was a brilliant lyricist, educator and critic. He resonated with the sentiments of a nation whose values were distorted and strained by 450 years of western domination through colonization.

Gerald Wickremasooriya of Sooriya Records phase-shifted Chorus Baila into the age of rock ‘n’ roll with electric guitars, drum kits and synthesizers. Since Bastiansz, Baila has evolved through different styles sung by soloists/groups and travelled overseas with the Sri Lankan diaspora. The dynamics of Baila has reinforced its popularity as the changing tastes of generations fluctuate and unfold. As Sri Lanka discovered and explored her post-independent identity, Baila became more enmeshed in the matrices of her indigenous cultures.

Chorus Baila is neither an import from Portugal nor a genre that was introduced by the Portuguese. Chorus Baila compositions were influenced by the Afro-Portuguese genre Kaffrinha and Vāda Baila. Chorus Baila signifies a new post-colonial identity, resonant with the recently independent nation of Sri Lanka. Bastianz felt the feelings of the people and voiced their sense, struggle and desires through his compositions of Chorus Baila.

The African contribution to the Sri Lankan culturescape and social life is very much alive in its music and dance genres. Afro-European links of Kaffrinha and Baila are rekindling an interest in the music of Sri Lankans with African and European ancestry. Whilst the various contexts of the kaffrinha remain to be explored through further research, the African roots of kaffrinha is clear.

An island not a petri-dish; roots and culture

Although the music of the largest surviving Afro-Sri Lankan community on the island is presently in Sirambiyadiya (Puttalam), it is not Kaffrinha (although often it is mistaken to be), but Manha. Lyrics of Manhas are mostly in Sri Lanka-Portuguese creole, the melodies are distinct from the Batticaloa Cantigas (songs) and Kaffrinhas. While the Creole that they once spoke is almost extinct, it is still the primary language used to transmit their oral histories through music. The Sirambiyadiya Kaffir’s chant-like songs, known as Manhas, are probably the most traditional of Kaffir music, and has experienced a revival of public interest in recent times. It is polyrhythmic with very few lyrics, passed down orally by their ancestors. It usually has 7 or less lines, repeated over and over again over percussive instruments, “we sing songs about love, the sea, animals, birds and devotional songs.”

They play a pink three-stringed long-necked wooden mandolin with a trapeziform resonator, drums, and found-object instruments: a glass bottle with a metal spoon, two coconut halves and a wooden stool or a metal vessel with two wooden sticks. It is usually played with a 12-piece band and sung in the original Sri Lankan Portuguese Creole.

The songs can sometimes last up to an hour, starting with a downtempo chant, gradually crescendoing into an ecstatic fervor of drumming, singing, clapping. The Sirambiyadiya community’s identity is entwined in their manha performance. Manhas are living testaments of the African diaspora in Sri Lanka and to the historical African presence on the Island.

Today, the Afro-Sri Lankan influence can still be heard in modern Sri Lankan music. Their unique blend of African and Portuguese elements has inspired many contemporary musicians, like Nimal Mendis (particularly in his use of polyrhythms and call and response), and Clarence Wijerwardena (in his approach to vocal harmonies and improvisation). The Afro-Sri Lankan contribution to the island's cultural milieu needs to be recognized, celebrated and preserved. The various nascent music scenes bubbling up in the island need to engage with our Afro-Sri Lankan musical heritage and communities in fresh and engaging ways, perhaps in ways similar to the jazz and classical Hindustani drummer Sarathy Korwar and his engagement with the music and peoples of the Siddi communities in India (producing a stellar album for Ninja Tune, while highlighting the plight of these communities in the cultural conversation). Perhaps now the internet will also sway the trajectories of musical evolution in Sri Lanka to broadcast, sprinkle and reap this heritage in even more unpredictable, yet equally exciting ways.

Listen:http://www.infolanka.com/miyuru_gee/albums/kaffir/

The information for the article above has been primarily sourced from the precious work done by Dr. Shihan de Silva Jayasuriya on Afro Sri Lankan communities and history.

By: Benny Lau

February 2023