Príncipe Discos: Our Favourite Records

“Push the envelope, watch it bend” (from Lateralus)

It is entirely plausible that the artists of Principe Discos do not approach what they do as primarily ‘pushing the envelope’ (admittedly a loaded term in itself), as they probably live and breathe this music every day, from bedrooms studios to pulsating weekends at MusicBox. But for the rest of us from all around the world, circa-2017, it has been an episode of Prison Break. An episode in which we imagine ourselves being finally freed from the doldrums of grayscale techno, top 40 radio, youtube house, Boat Parties, hypersexualized hiphop & rnb, and ordering music online (and whatever else was trending at the time). This envelope was being sealed and delivered, in unbeknown ways, to unknown parts, for unknown pleasures. As the label co-founder Pedro Gomes notes:

"This music has something that most music in the West does not have, it has a truly profound inter-continental appeal. This can work in Africa. This can work in all of Latin and North America, in Asia and, of course, in Europe. This music has been brewing for centuries, through the slave trade, through immigration, and now through digital technology. Fruity Loops is a miracle for this secular brewing process, because finally you get this pristine percussive complexity translated directly to digital and then onto the vinyl. Now you can finally translate all these centuries of rhythmic advancement. Because it has that kind of richness to it, it can work. Because it's been brewing for so long, it can work anywhere. But it's not populist. It's not global in the sense of United Colours Of Benetton bullshit. It just works. People just react to it."

Based in Lisbon and founded in 2011, Príncipe Discos has been dedicated to showcasing contemporary dance music emerging from the city's suburbs and marginalized communities. The label’s aim has been to amplify the unheard voices and unique sounds of Lisbon's underground music scene, under the broad umbrella of batida, that including genres like kuduro, kizomba, funaná, and tarrachinha; characterized by new sounds, forms, and structures, with their own poetic and cultural identity. Márcio Matos, one of the label's founders, hand-paints and stencils each record, making every copy unique with a distinct DIY feel. To cap it all off, Príncipe has been fostering a close-knit community through its legendary "Noite Príncipe" parties at Lisbon's Musicbox, where artists test out new material while the label scouts new talent. Nearly 15 years later, it seems like nothing has changed.

As we get ready to host #13 with one of Príncipe’s finest (Nuno Beats), we mulled over (13 of) our favourite records from the label. The records were picked to cover both stylistic breadth and historic(al) progression of the esteemed institution (whilst leaning towards longer-players over singles/12”s) – thus potentially, a good entry point for the uninitiated.

V/A – Dj’S Do Guetto Vol. 1 (2013)

Considered a foundational piece in the development of what we know today as batida, the compilation (now a cult classic) was originally released in 2006 by a group of young DJs from the musical hotspots surrounding Lisbon. It was later re-released in 2013 by Príncipe, revealing the early dynamics of the scene’s salad years to a wider audience. The music within, characterized by its breakneck, complex rhythms and underscored by percussive intensity and sonic texture, helped establish Lisbon as a hub for electronic music and brought attention to the talents of Marfox, N.K., Pausas, Jesse and the legendary DJ godfather– Nervoso.

A towering figure of the Príncipe camp, Nigga Fox’s 2013 debut arrived like a bat out of hell, to shock-and-awe the system. Translating to “my style”, the EP contains fearless beat workouts from one of the best in the business: the hypnotic “Hwwambo”, the propelling “Powerr”, the marching “Weed” and the trippy “O Badaah”, four tracks that could dismantle any dancefloor on any given Friday. Accordions, violins, buzzy synths, teacups, wild chants – it’s all here, but cushioned by the tactile fibrocartilage of Fox’s polyrhythms.

DJ Firmeza seems to be a master of percussion – minimalist in scope, maximalist in impact. Objective: to cook up raw percussive stabs into a woozy, hypnotic frenzy. Melody is sparse, and whatever remains (strings, flutes and vocal samples) drift around in the mix only to aid and abet this exercise, having only one thing in mind (“beat sex”). The title track, a prime example, morphs into a 6-minute cyclone of immersive rhythm.

An icon in Lisbon’s bubbling club circuit even before his Príncipe days, DJ Marfox is the figurehead around whom the label found its footing (note: Marfox is the first artist to sign for Principe, kicking it off with the Eu Sei Quem Sou EP). Chapa Quente, his second outing on the label, is laser-focused on the floorboards, with 6 tracks of high-octane heaters: “Cobra Preta” is a ridiculous World Party, and the “Kassumbula” is straight voodoo business.

DJ Lilocox – Paz & Amor (2018)

DJ Lilocox – Paz & Amor (2018)

Acknowledged as a breakthrough release at the time, Paz & Amor contains deep atmospherics and relentless groove. Its sound leans towards tribal and afro-house, maybe a testimony to its wider appeal. An integral member of the Príncipe camp, Lilocox builds massively spacious pads within a haunting, widescreen soundscape. Sprinkled on them are rattling handcrafted drumwork – a winning combo: an intriguing intersection of batida and house music.

Niagara – Apologia (2018)

Niagara is a band of worldly influences, and they add another dimension to the Príncipe catalogue. Apologia arrives as slow-burning, psychedelic immersion, not dancefloor detonation. The album's strength lies in its textural depth: intricate soundscapes built on crystalline arpeggios gliding over distorted guitar and manipulated vocals. Tracks like "Sangue Bom" and "Húmus" unfold at almost glacial pace, demanding complete dominion. There's a tangible sense of analog warmth, a feeling of tape hiss and circuit-bent experimentation that lends things an organic feel. It's a sound that feels both futuristic and oddly nostalgic, like a radio transmission from a forgotten era. A singular album nestled in a special corner of the label.

Nigga Fox’s second entry on the list is also one of the catalogue’s finest: It seemed that with Cartas Na Manga Fox discovered a secret extra gear – tying up the Kuduro with few more layers of jazz, techno, acid (and congas) into a woozy, melted hotpot of rhythm. The beats here are high-speed and headlights-on, and rolled up in jazzy horns, pinging piano, steely clangs. In 2019, very little else sounded like this. Too early for Modern Classic status?

Founded in 2016 in Rinchoa, RS (Rinchoa Stress) Produções is a crew of Portuguese artists that include DJ Narciso, Nuno Beats and Farucox Beats, and their second full-length album is one part dancefloor-heat and one part jagged-melancholia. The sequencing of dizzying batida juxtaposed with soft tarraxho makes for special listening, from the chirping grooves of “ORACAO” and “ARMADILHA” to the brooding blues of “Valentines Day 2K17” and “Sem Cabeca”, not to mention the g-funk of “PrinCIPES”. A long player, range wide.

Moody, pensive, delicate Batida, weighted just right. DJ Danifox laces Ansiedade with his intriguing vox, cinemalike chords, Robert Johnson guitar, and probing bass notes that hit deep and wide. 100% groove and 0% clutter, with near-perfect spatial arrangements. Old world charm. Slow, swinging club music that sounds like an intimate Tropicalia classic from the 1960s (Caetano Veloso?). Sublime.

Nuno Beats – Sai Do Coração

Nuno Beats – Sai Do Coração

RS Produções mainstay Nuno Beats seems wise beyond his years: Sai Do Coração is cool, shimmery soul, made with a sage, scholarly touch. He explores the other side of the batida coin effortlessly, with the flair of the slickest of operators. From its Drexciyan melodies and longing chords to feet-dragging drums. Basslines bubble up in your ear. Late night tales. A dash of Patrón, chased with lemon drops. Pure silk.

Nídia – 95 Mindjeres (2023)

Nídia – 95 Mindjeres (2023)

Nidia Minaj is a star. On 95 Mindjeres (“95 Women”), the kinetics of Batida and Tarraxho is refracted through a prism of deeply personal and historical narratives. The understated low-end, rather than simply providing a foundation, acts as force, shaping the sonic contours. Subtle shifts in texture and spatialization create a sense of constant movement. The album's dedication to the women fighters of the PAIGC gives it all a sense of historical resonance. And storytelling.

DJ Lycox – Guetto Star (2024)

DJ Lycox – Guetto Star (2024)

By: DJ Infrastructur

March 2025

Sweet Tapes x 925 (ST004)

“925 Colombo controllers mdj and ABDC present a fiery sambol of a tape, primed to be dropped at your next cassette deck-rigged dinner party.

side A works a holistic mix of ethereal hip hop, smoked out dub and grime with a zing of lime, with flavours so big you won’t know if it’s the hit of the sub or the finely balanced spices in the thaali.

the flip comes infused with creamy coconut breaks and a heady techno arrack known to induce mouth frothing, head nodding and cries of oioi: behaviour unbefitting of a formal social gathering perhaps, but we’re among friends — grab a plate.

includes:

— 1x c90 audio cassette 📼

— 1x zine tracklist 📗

— audio download ✨

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

all profits will be donated to Camp Breakerz Crew, Gaza”

side A works a holistic mix of ethereal hip hop, smoked out dub and grime with a zing of lime, with flavours so big you won’t know if it’s the hit of the sub or the finely balanced spices in the thaali.

the flip comes infused with creamy coconut breaks and a heady techno arrack known to induce mouth frothing, head nodding and cries of oioi: behaviour unbefitting of a formal social gathering perhaps, but we’re among friends — grab a plate.

includes:

— 1x c90 audio cassette 📼

— 1x zine tracklist 📗

— audio download ✨

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

all profits will be donated to Camp Breakerz Crew, Gaza”

By: ABDC

June 2024

Gavsborg: A Hit Piece

Equiknoxx Music is an institution, with a wonderfully sprawling catalogue which is a testament to their adventurous, feed-forward sound. Gavsborg and (co-founder) Time Cow, along with Shanique Marie, Bobby Blackbird and Kemikal, have almost single-handedly flipped the script on what is possible within (and beyond) the confines of what made dancehall great.

In anticipation of his debut Sri Lanka show on 24 February 2024, we hand-selected 10 of our favourite songs from the Gavsborg (and Equiknoxx) multiverse, carrying the rhythm touch of one of the most singular, creative minds in music.

Make that 11.

In anticipation of his debut Sri Lanka show on 24 February 2024, we hand-selected 10 of our favourite songs from the Gavsborg (and Equiknoxx) multiverse, carrying the rhythm touch of one of the most singular, creative minds in music.

Make that 11.

Unkle G & Gavsborg – Unkle G [An Honest Meal]

The title (character) track that expands on the fascinating Gavsborg (alter ego) Unkle G (note: a great introduction to Gav himself). The trials, tribulation and tabulations (i.e. scores) deadpanned over a bed of patiently built keys and extra-extra horns: In the studio. Every day, every day.

Kat7 – Rubadub Skank (Feat. Irinia Mossi) [Motherboard]

Kat7 – Rubadub Skank (Feat. Irinia Mossi) [Motherboard]

A highlight from Motherboard, the spunky debut LP of Kat7, a collaboration between Gavsborg and reggae artist Exile Di Brave. A rudeboy hit that effortlessly involves the Swiss-Congolese singer Irinia Mossi in the mix.

Equiknoxx – Manchester [Eternal Children]

Equiknoxx – Manchester [Eternal Children]

An Equiknoxx (and modern) classic at this point, paying homage to the time Equiknoxx spent in the famed city of legendary musical heritage. A UK-Jamaica mind-bassline intersection.

Equiknoxx – Urban Snare Cypher [Basic Tools]

Equiknoxx – Urban Snare Cypher [Basic Tools]

A standout from their latest LP (Basic Tools), “Urban Snare Cypher” is a textbook exhibit of Equiknoxx sound: space, torque, and tough basswork. (Listen on headphones, cranked up to 13).

Unkle G & Gavsborg – Popcaan Said My Riddims Aren’t Good [An Honest Meal]

Unkle G & Gavsborg – Popcaan Said My Riddims Aren’t Good [An Honest Meal]

A ferocious, cinematic tour-de-force dripping with signature Gavsborg humour and um, shade.

Gavsborg – Coming to Your Grey (feat. Shanique Marie) [1 Hour Service]

Gavsborg – Coming to Your Grey (feat. Shanique Marie) [1 Hour Service]

From his ghetto-psychedelic debut on Casstte Blair (1 Hour Service), where Shanique Marie matches haunted atmosphere and snare energy with equally yielding vocals. Wouldn’t be out of place on a Sound Signature 12 inch.

Equiknoxx – I Really Want to Write Her Purple Wall [Bird Sound Power]

Equiknoxx – I Really Want to Write Her Purple Wall [Bird Sound Power]

From the Equiknoxx’s debut album that arrived like a bat outta dancehall hell, and laid the foundations for their taut and steely sound, that slowly evolved into a polyhedron prism. Along with “Last of the Mohicans”, “The Link”, “Timebird”, “Congo Get Slap Like” (and more) – cornerstone of a sleeper classic.

Time Cow & RTKal - Elephant Man [Elephant Man]

Time Cow & RTKal - Elephant Man [Elephant Man]

A track with a great backstory, of a night in Kingston lauding the impact of the eminent Elephant Man, that ends “with the ghostly synth + drum repetition concocted by a volca beats trial run by Gavsborg”.

Equiknoxx – Melodica Badness [Colon Man]

Equiknoxx – Melodica Badness [Colon Man]

From their sophomore album, Colon Man. Another riddim of elephant (man) proportions.

Equiknoxx – Someone Flagged it Up!! [Bird Sound Power]

Equiknoxx – Someone Flagged it Up!! [Bird Sound Power]

Equiknoxx at their most sublime, combining Kingston gunfya urgency with stunning Basic Channel bassline flow (with an apt remix from the great man himself).

Equiknoxx – Uggh (feat. Joey B (Mcr)) [Basic Tools]

Equiknoxx – Uggh (feat. Joey B (Mcr)) [Basic Tools]

Gavsborg will perform at 925 Colombo on 24 February 2024.

By: DJ Infrastructur

February 2024

Reflec - 5 Tracks

Ahead of his 925 Colombo debut, the UK producer

picks five of his favourite tracks currently in rotation.

Derrick May - Spaced Out [1998]

Derrick May - Spaced Out [1998]

A classic from the Detroit pioneer. Can

listen to the riff over and over without getting bored – epic synth work and

groove with slight detune.

Swimful – Muckle [2021]

Swimful – Muckle [2021]

Shanghai-based producer from the UK.

This leans more towards a dancefloor track than a drill instrumental – too much

going on for someone to put vocals over this.

Menchness - Mitsubishi Song [2015]

Menchness - Mitsubishi Song [2015]

Had to include a Memphis tune – synth

on the beat is unreal. La

Chat is also great rapper.

Young Nudy – Peaches & Eggplants

feat. 21 Savage [2023]

Favourite trap producer at the moment – Coupe.

By: Reflec

January 2024

ACID. The carboard separator read in big, bold letters. It was a drizzly Tokyo evening, and I was at Technique, the infamous Japanese record store (now defunct). Inside a lowly-priced basement bin, lay a 12” carrying an obscure Tin Man remix. There was a line of record players along the windowsill. I put the needle on the record, not knowing the full story at the time. Mayhem ensued, rain shards coming down on the glass at an incline. As did the (s)tabs of acid – A fascinating name, a fascinating genre, a fascinating device. But what of it?

Tin Man (real name Johannes Auvinen) is one of the best to ever do it on the Roland TB-303, the (posthumously-deemed) genius Japanese bass synthesizer that transformed techno and house music as we know it. Born in California and based in Vienna, Johannes is known for his mastery of all things acid, the subgenre of dance music born out of Chicago and the 303, in early to mid-1980s. In a way, perhaps acid was to dance music what new wave was to rock music, an extension cord that expanded the original blueprint, while managing to crossover to a wider audience in its heyday and power few other exciting subgenres too. The Roland 303 was what made it possible: Combining house and techno music’s four-on-the-floor beats with its signature ‘squelchy’ basslines, acid house birthed a fresh sound for dance music where the focus moved to sonic texture and atmosphere. The unique, undulating sounds were made possible by creating variation in the 303’s bass pattern output, by manipulating its filter resonance, cutoff frequency and octave parameters.

“The most unique sound of the history of the world” is how DJ Pierre describes the 303 (as Acid Tracks would testify). One third of seminal Phuture, (the early adaptors of the 303, along with Charanjit Singh, Alexander Robotnick and Sleezy D), Pierre reveals that their quest to “create a sound that was different” in the early 1980’s ended with their discovery of this Roland synthesizer. Designed by Tadao Kikumoto, Chief Engineer (and Managing Director) of Japan’s Roland Corporation at the time, its original intent was to act as a bass synthesizer that simulated the bass guitar (Tadao was the Chief Designer of the TB-808 and the TB-909 too). The TB-303 was a commercial failure, however, and was discontinued within 3 years of unveiling in 1981. Incredibly, Tadao and his team only heard about the 303’s influence on underground music more than 10 years later, through a “well-informed guy from an overseas department.” Since then, from Orbital to Plastikman and Aphex Twin, from LFO to Daft Punk and Timbaland, the synthesizer has forged a path of its own. “Every twist and turn…never to be heard exactly the same way” DJ Pierre recaps, referencing the inimitability of this almost-chance intersection of machine vs sound.

Acid house’s broader influence cannot be underscored, its ubiquitous tentacles seeping into several future styles of electronic dance music (from jungle to triphop), while at times transcending it to inoculate the orbit of pop music too. Its early purveyors included promoters and artists of Ibiza circa ’87, as well as the Second Summer of Love and ‘Madchester’, which were uninhibited music and rave movements that defined UK’s music scene and club culture for years to come. This passage of time carried the same free-spirited verve and anti-establishment leanings of the hippie movement of 1960s San Francisco, powered by the newfound sound of acid, resonant warehouse settings, charming fashion and the liberal use of MDMA. In the meantime, legendary artists such as Baby Ford, Adonis, Mr Fingers, A Guy Called Gerald, the KLF and 808 State, Aphex Twin and Josh Wink took the acid house sound in further exciting and compelling directions.

Fast-forward 15 years, Tin Man arrived, at a slightly different phase of underground dance music (around the time of microhouse, M_nus mnml and French house) or in fact, independent from it. A precision technician and a refined songwriter, you would think the machine (the Roland 303) would be scope-limiting for Tin Man, but the opposite is true. “It is amorphous and abstract, yet has a narrative quality that transports you”, he says of acid. In the process, Auvinen has not only seized both the genre and the device, but reimagined their (increasingly worn-out) direction at the time, to traverse a world of U-shaped valleys and troughs: Observable but not yet fully explored territories, for both machine and man (with a little help from other gear too, of course).

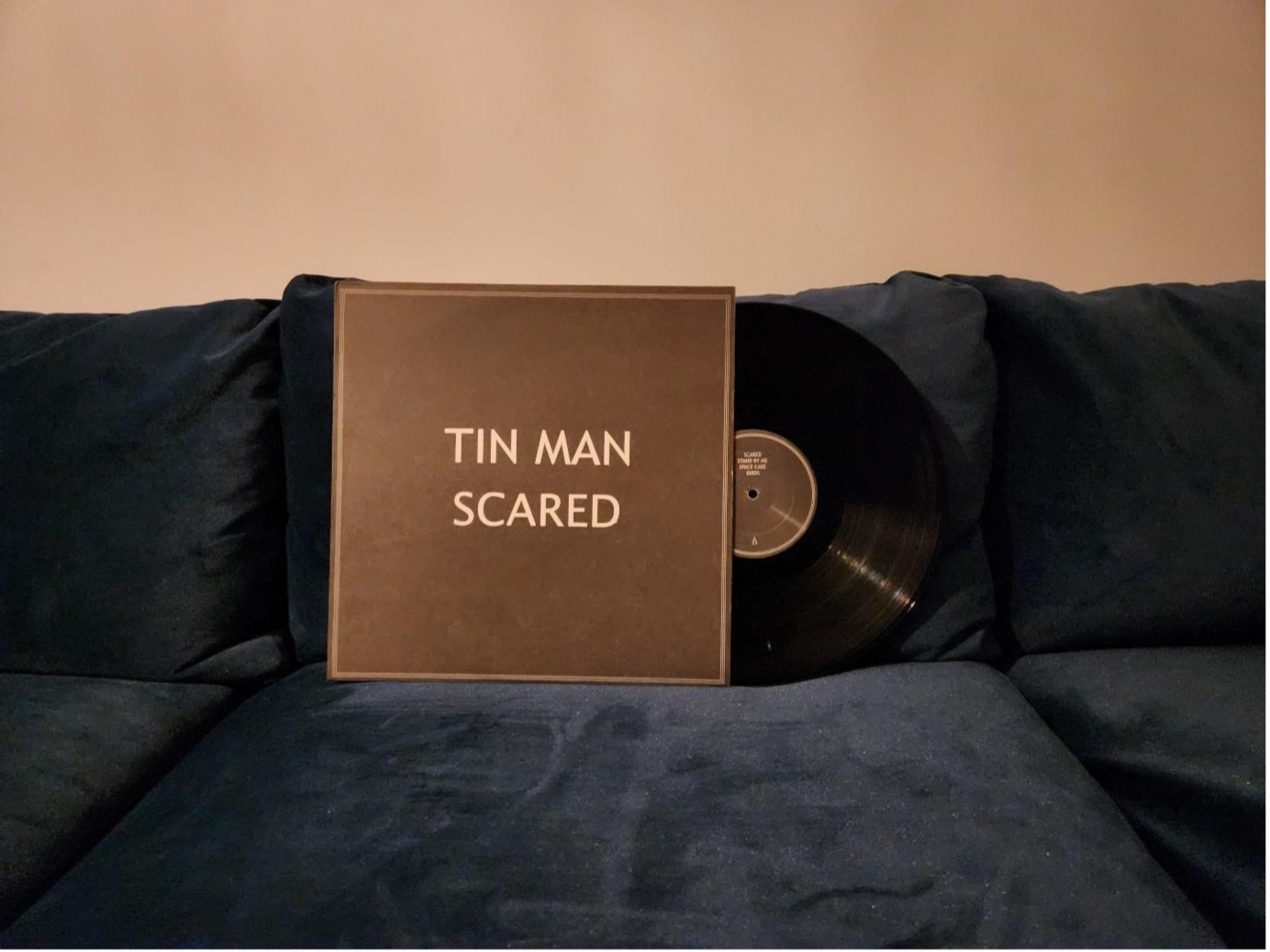

Let’s start with the LPs: Acid Acid (2005) was foundational – barebones analog workouts that marked his arrival. Wasteland’s(2008) drony electronics took things towards an icy Detroit-Chicago nexus. Scared (2010) combined (opinion-dividing) vocals with moving, Ambien-induced drama (and at times, dread). Perfume (2011) was more vivid vox house, jazz-club at worst, radiant at its best. Vienna Blue (2011) reinvented the wheel (again), with a ‘winter album’ of classical strings, chamber music and romance. Vocal-less Neo Neo Acid (2012) felt like a crucial landmark, distilling the Tin Man essence into vintage understated melancholy. Ode (2014) amplified the kickdrums, basslines and ‘dark matter’, marching things towards a dub-techno basement. Dripping Acid (2017) funneled 17 immaculate cuts (of the 12” series) of urgent, pinging, frenzied and at times otherworldly acid techno, with Tin Man in his most relentless, cohesive element. Arles (2023) subdued the acid and channeled the forcefield towards serene, cosmic electronica.

(Continuing this dense rundown), then there were the 12”s (and collaborations): Love Sex Acid (2006) was a lush spiral staircase, Luomo-meets-Mr Fingers. Keys of Life Acid (2006) contained the life-altering “Tip the Acid”, a portal to the 303 afterlife. Acid Test 01 (2011) yielded “Nonneo” and the rarified Donato Dozzy remix. Meanwhile, Tin Man’s shadowy collaborations with artists such as Gunnar Huslam (as Romans), Foreign Material and Cassegrain have explored the uncanny nooks of these soundscapes. Dov’s anthemic Silent Cities (2019) (with Mexico’s Gabo Barranco) and Ociya’s Power of Ten (2020) (with Patricia) were unheralded gems, the latter’s IDM-tinged tracks recorded live with apparently barely any editing. Rolling Ones (2016) (with Jordan Poling) were deep-sided burners, powered by vintage locomotives. Acid Test 11 (2016) (with Josef K and Winter Son) gave “Fates Unknown” and “Pendle By Night”, that capsuled the existential unrest threaded through most of the Tin Man catalogue.

The best things are borrowed. Tin Man seems to hold a shared vision of music than most (“the history is always that everything's taking from other places”), understanding (and even embracing) the cyclic nature of things: He has quietly pushed the envelope of acid, knowing that what is good has always been built on what came before. Beyond songwriting, he seems to be committed to a uniquely spatial sound design – maybe why everything sounds this good, his studio endeavours aiming to model a user experience that confounds. Similarly, ‘meaning’ has hung in the air ambiguously, in both word and melody, in an unusually comforting nexus. There’s an Overman quality to it all, standing alone from the pack, singular in mission: An admittedly committed participant of a (vaporous) underground, yet careful not to be defined by it.

Hidden Acid EP, Released in September 2023, marks Tin Man’s return to 303-centered label Acid Test after 5 long (and lonesome) years. It’s a return to the base, after range-defining outings towards ambient and electronica (and resting his fans fears of selling off his hardware online – as one reassured – maybe it’s just housekeeping?). On Hidden Acid, Tin Man seems to negotiate and wrangle every drip of emotion out of the machines: “Running Acid” is a moody nightbus jaunting around town, its lead synth arpeggio bobbin’ and weavin’ around some (club-destroying) acid-traffic, intensifying by the minute. “Hidden Acid” is part G-funk, AFX and a 90s brickhouse rave – when a doused snare lands two minutes in, you are already busy Trainspotting. The pensive closer “Wrapped Up Acid” laces more Roland spliffs around a chord-choir and shifting drums. The feelings are full-scale but never precious – everything seems to operate within a certain circadian rhythm (as captured by the artwork).

Although he has made great music all throughout his career (despite the limitations originally perceived of his um, field), it felt like the 2011’s Neo Neo and the “Devine Acid” era transcended the borders of acid house, through sinuous melody-stories that permanently infiltrated your subconscious mind, and somehow, hijacked the dancefloor too. “Swaying Acid” seems to be of the same DNA: dazzling congas and 303-voodoo dribbling around glistening platinum pads – pads that everlast, and bleed into new borderlands. Too much acid. Sweeping, sublime acid.

By: Tarifa Banks

January 2024

Masicka, “Tom Brady” and the Future of Dancehall

In our latest, we take a look at Masicka and modern dancehall, as the young artist from Portmore Jamaica continues his godly run. Is he the heir to Vybz Kartel’s throne? Time to find out.

![]()

Sometimes it feels like the globalization of dancehall and afrobeats (and convergence of genres in general) is making everything sound monolithic. Is the maverick spirit that characterized some of the more rhythmically fierce, risque and ‘original’ hits, pre-circa 2015, slowly being overrun, nearly a decade later? Is the sweet-talking Pop Music Machine threatening to flatline the rough and thrilling spikes that made these genres exciting? Dancehall records, compilations, and bootlegs (abundant in decades pre-2010) are becoming increasingly harder to press, alluding to the economics and technology that dictate modern music consumption, and the soundsystem and dubplate culture that birthed it. Today, we have tech behemoths – from Apple Music to Spotify to Youtube – dictating the flow of your next find, overproduced and compressed at 256kbps. Technology, and its influence, from congeneric studio software to AI algorithms, seems to have a levelling effect on the music.

That is an outside-looking-in view, and an unfair representation, a rude generalization, of someone like Masicka – the dancehall deejay from Portman Jamaica who recently signed to Def Jam, and who seems to retain the same mad-max moxie that made him an exciting (and perhaps generational) talent at the time. In a primarily singles-driven genre, his debut album landed to box office triumph at the end of 2021, whilst his grand follow-up album was unveiled in December 2023. Even more so, a slew of singles that both predates the new album, foretells an arc of an artist on the cusp of unlocking a new level, and marrying artistry with that often-elusive thing — reach.

When measured on the metrics of output and influence, the last decade feels bright for dancehall and Jamaica: Breakout stars Shenseea and (grammy-winning) Koffee turned lockdown blues into crossover success (the latter to critical acclaim); genre superstars Sean Paul and Popcaan made compelling album content; industry veterans Spice and Charly Black released their long-awaited debut albums; reggae talents Chronixx, Protoje and Kabaka Pyramid built on their dancehallfooting; smooth operators Kranium and Konshens retained their Midas touch for hit records; amazing vocalists Lila Ike and Jada Kingdom continued their rise; super-producers Rvssian and Dre Skull expanded their reach (the former into pop & reggaeton, the latter into well, everything good and pure); cross-genre and cross-continent hit songs dominated global airwaves; and the weird & wonderful Equiknoxx kept pushing unforeseen boundaries inside the ‘dungeons of dancehall’. All of this, whilst the King remained as prolific as ever, striving to stay dominant from prison (but more on him later).

![]()

As the initial spark of ska and rocksteady morphed into reggae music, Jamaica’s flag was firmly established as a music powerhouse in the 1960s. If population was weight, the country was not only punching above its weight-class, but redrawing the boundaries of the ring. “No song, no dub”, yet it could similarly be argued that no other genre has had a wider impact on modern music than dub music, the mutant offspring of reggae. Was it something in the soil? Was it the island’s penchant for adventure? Or its revolutionary spirit? Was it the genius of Lee Scratch Perry and King Tubby? Or all of the above? In the midst of this, dancehall was born, as a counter-movement by (and for) working class inner city Jamaicans who were shut out from ‘uptown’ parties. Dancehall events were new, visceral experiences for its audiences, with low bass frequencies, earthshaking volume and ‘digital’ gyration cranked up to level 11. Even more so, it levelled the field by bringing ‘people’s music’ directly to communities who did not possess radio, and to artists whose music was not played on the radio. There was an invigorating quality to the music, with its gritty and primal depiction of day-to-day subject matter, compared with the more ideological roots & reggae movement.

![]()

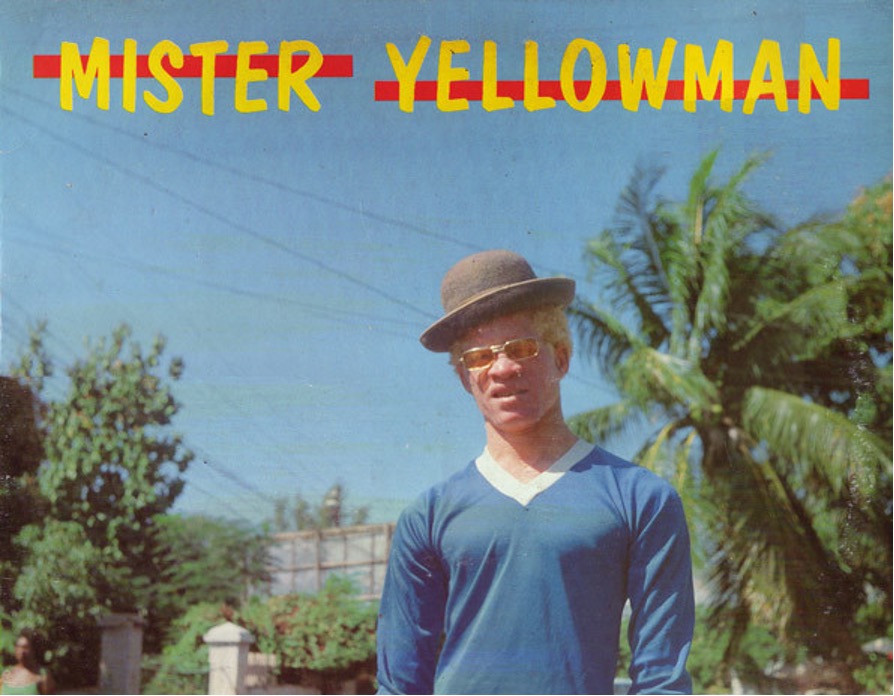

At the center of this was the physicality of the sound itself, via soundsystems such as Black Scorpio, Silver Hawk and Killimanjaro. Together with the soundsystems, dancehall’s early torchbearers were artists such as Captain Sinbad, Clint Eastwood, Yellowman, Charlie Chaplin, Sister Nany and Lady Saw (and “Sleng Teng” Riddim by King Jammy and Wayne Smith). Yellowman in particular was a fierce proponent of the genre and its ethos, and became one of its first superstars. In the 1990s, the next wave of artists such as Beanie Man, Buju Banton, Mad Cobra, Bounty Killer, Shabba Ranks, Capleton and Elephant Man, who along with a new school of producers such as Dave Kelly, Bobby Digital and Ward 21 sharpened and glistened the riddims with the use of electronic synthesizers and sampling. The arrival of Sean Paul in the early 2000s brought even more mainstream recognition, an international dancehall icon who was able to capsule the fun and immediacy of the genre, whilst being able to retain his songcraft, relevance and longevity in a changing landscape.

Fast forward a decade, when Dre Skull produced Vybz Kartel’s electro-tinged Kingston Story LP in 2010, it potentially marked a pull away from singles into more cohesive long-players. Equally talented Rvssian perhaps signaled the arrival of a pop genius (but one who seems to have surrendered the raw energy of his early work for grander ambition). Since that time, the dancehall hit machine has been chugging along in the last decade, both inspired and uninspired in equal measure, whilst recently being associated with different movements – from (the more colourful) Africa and the UK, to (the more monochrome) trap-dancehall, pop music and ‘tropical house’. Dancehall’s global influence has been unmistakable: from Rihanna and Drake to Jaimie XX and the ‘biggest track on youtube’ (where Justin Bieber characterized the obvious dancehall influence as that of “island music”). You cannot help but think that the heavy lifting done by dancehall over the years to bring its signature syncopated flavour to the orbit of mainstream music, has not received its due flowers. But everything moves in cycles, and the (often valid) fears of expropriation by the West and the (sometimes unfair) overshadowing by a rising Africa aside, dancehall is still alive, kicking. As one astute observer remarks on La Lee’s bracing “Dirt Bounce”, “Dancehall nice again?”

![]()

In this cosmopolitan landscape, inspiration on where dancehall could sonically go, is perhaps hinted by a few producers on the frontline of Jamaica’s reggae and R&B scenes: Sean Alaric combines dub pulse with immersive atmospherics on work with Lila Ike, Jesse Royal, and Khxos (and this Burna Boy remix). J.L.L. brings inspired instrumentation and sampling to his work with the emerging talents of Jamaica. Koffee and Jorja Smith producer IzyBeats may have cracked the ultimate slowburner code. A new generation of stunning songstresses are brewing and bubbling just underneath the surface (Shenseea, Jada Kingdom, Lila Ike, Jaz Elise, Naomi Cowan and Sevana are all great vocalists). Natural High Music revive sound-system culture through their ‘future roots’ sound with a rich palette behind the boards. Equiknoxx maybe the most intriguing of them all, over the course of a decade, moving beyond their early dancehall hits to build a planetarium of sound ideas: Their penchant for leftfield instruments and sampling methods has organically expanded their sonic canvas, whilst their growing worldwide network (including some O.G. links), features on heady labels and events and curious side projects have yielded rightful acclaim. In the intro to “Blessed” dancehall legend Buju Banton offers some words of wisdom to Koffee. The hope is that the new school of artists can continue to ignite that brisk and bouncy spark-up, while retaining its Jamaican identity, that make ‘the dance hall’ such an exciting movement.

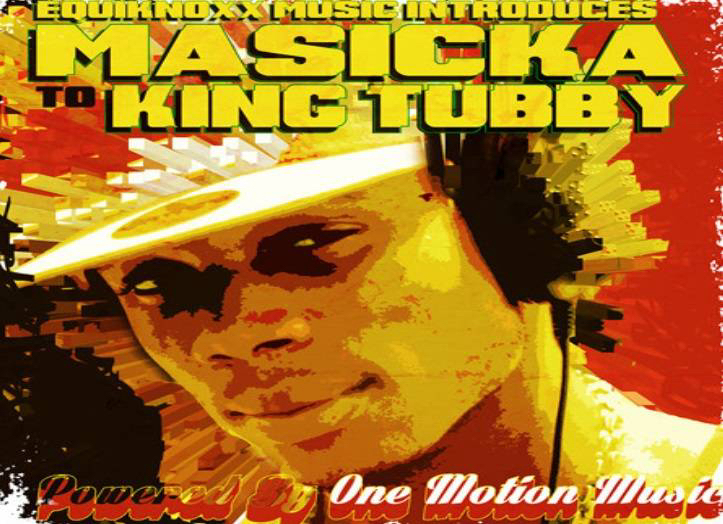

And one of them, is Masicka. Bursting on to the scene in 2012, Masicka (real name Jauvaon Fearon) hails from Independence City, in Portmore Jamaica. He first rose to prominence through songs that gained traction on local radio stations whilst still in Kalaba High School (“Guh Haad N Done”, “Lose Control” and “Whistling Clean”). His sessions with Equiknoxx (the first of which he secured by winning a DJ competition while in High School) are an interesting body of work, harking back to the salad days where Gavin Blair’s eccentricity brought out something alike in Masicka. The cult-favourite 2012 EP Equiknoxx Music Introduces Masicka to King Tubby is a curious artifact of a brazen young deejay spitting new-school rhymes over timeless dubs, a sign of a things to come at the time. Since that time, he has dabbled in more conventional dancehall, with One Motion Music, Genahsyde (his own imprint) and producers such as Dunw3ll. Fast-forward to 2023, the older-and-wiser Masicka has been on a lethal run of singles.

![]()

It’s a run that started around the ‘carbon-rifle rhymes’ of “God Damn”, and continued on with “Drug Lawd”, “Grandfather”, “I wish”, “Pack a Matches”, “King”, “Feisty”, and culminated with the “Tom Brady Freestyle.” The latter contains arguably the most efficient use of Bars since Juelz Santana launched his helicopter-flow, the deadly economy of lines like “Mi gun nuh feel safe wid safety”. Carrying the weight of a timeless sportsman of the modern era, the track does justice to the tag. On the simmering “Update”, Masicka stands back and commands the sonic space over an earthmover bassline, while letting out barks and squeals that momentarily push his voice into 3-octave territory (ha). The track is a powerplay in spatial dynamics, a nod to heavy-duty dub as much as dancehall (“Spend a couple dubplate, make the club shake”), its shoutouts still ringing in the ear after the music ends.

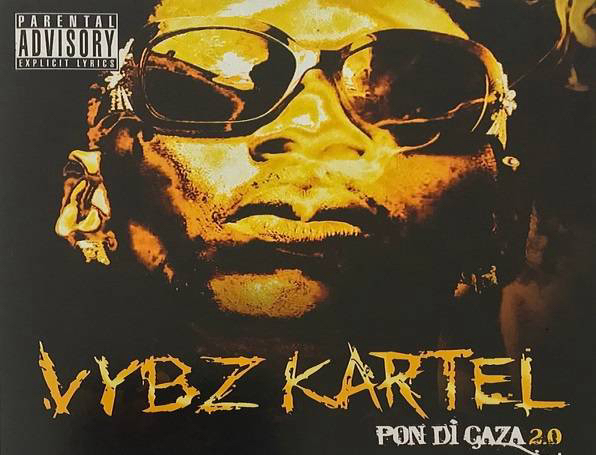

The non-dancehall heads may have discovered Vybz Kartel, widely regarded as the greatest dancehall artist of the modern era, on the eponymous “Diplo Riddim” (from Diplo’s Hollertronix-era debut ‘Florida’ of 2005). This was around the time of JMT, before “Romping Shop” and “Yuh Love” took the world by storm. What makes Vybz so great? It was even on display then: Bluster, street knowledge and charisma all curled into one injection-flow, that was able to navigate any tricky nook of a topic, in that commanding yet gregarious voice you intuitively gravitated towards (Note: Vybz has a great storytelling tone). An artist whose influence runs deep in Jamaica, Kartel’s scope was manifold – a lyricists who was able to do it all with an alluring swagger. And a songwriter who was so quick on the draw, that he has redefined the term ‘prolific’. Even after his conviction for murder in 2014, he continued to release music at a head-spinning rate. And through his label Portmore Empire, the MC also took under his wing emerging talents in the island, including notably Tommy Lee Sparta and Popcaan.

![]()

But if Vybz was the Di Teacher and Popcaan was the protege, the latter seems to have graduated from the streets and landed on pastures foreign, his sights set on a wider, more pacific world, rubbing shoulders with a global assembly of stars in the process. Maybe Popcaan was the joyous messiah dancehall needed, on a scenic bridge that crossed over to the town square – but one that still feels authentic, spiritually grounded and expansive. “Something about his voice…pulls you in, draws you in”, says Dre Skull. The Fixtape (the mixtape on soundcloud that accompanied the album proper) may just well be the dancehall statement of the new decade, an exuberant carnival on full-blast, that blurs the lines between a myriad of influences and serves up everything good and wholesome (note: watch an amusing piano-laden Vybz intro segue into a hair-raising cover of Nas’s “Hate Me Now”) In the end, you cannot help but feel the trajectory of Popcaan’s burgeoning career is decidedly less Badman – and more Poppy – than Vybz’s. And perhaps, all the better for it.

So where does that leave us? Even with an opaque incarceration spanning over 12 years, the question of ‘who is the Next Vybz’ is seldom speculated in dancehall circles, often ending rather bluntly (“there is no next Vybz” – and never will be). But on the scale of the gritty streetwise blueprint of Kartel’s best work, there is also Alkaline, and there is Skillbeng, trying to map out designs of their own. Alkaline started out frighteningly-well, but appears to have lost some focus along the way. Skillbeng, who potentially got the nod from Vybz himself, is the more obvious (and direct) comparison, with his piercing delivery, husky circles-around-you flow, and innate starpower. All three appear to possess something singular and special. With a sophomore LP that just landed, Masicka ‘Top ah di game/Tom Brady’ may just be on the inside lane. But can they regulate the paperchase, take calculated risks, and remain fierce? Either way, it’s bound to be intriguing viewing, for both Jamaica and the world.

925 Dancehall Special [Mixtape]

1. Vybz Kartel – Hey Addi [2016]

2. Vybz Kartel – Enemy Zone [2016]

3. Konshens – Purple Touch [2021]

4. Popcaan – Fresh Polo (Ft. Stylo G & Dane Ray) [2020]

5. Vybz Kartel – Loodi (Ft. Shenseea) [2017]

6. Sean Paul – Boom [2021]

7. Konshens – Bassline [2018]

8. Intence – Nuh Behaviour [2022]

9. Spice – Crop Top [2022]

10. Mavado – Bad Girl [2022]

11. Masicka – God Damn [2020]

12. Capleton & Black Brown – Wey Up Deh [2015]

13. Konshens – Gun Head [2021]

14. Popcaan – Bad Yuh Bad [2017]

15. Skillibeng – Prolific [2021]

16. Aidonia & Govana – Earthquake [2023]

17. Koffee & Govana – Rapture (Remix) [2019]

18. Alkaline – Twerc [2021]

19. Stefflon Don – Hurtin’ Me (Ft. Sean Paul, Popcaan & Sizzla) [2018]

20. Laa Lee – Dirt Bounce [2021]

21. Laa Lee – Tip Inna it [2020]

22. Masicka – Update [2021]

23. IWaata – Anyweh [2021]

24. Skillibeng – Stefflon Don (Ft. Stefflon Don) [2021]

25. Kranium - Life of the Party [2021]

26. Jada Kingdom – Fling it Back [2022]

27. Equiknoxx – Uggh (Ft Joey B) [2021]

By: DJ Infrastructur

December 2023

Sometimes it feels like the globalization of dancehall and afrobeats (and convergence of genres in general) is making everything sound monolithic. Is the maverick spirit that characterized some of the more rhythmically fierce, risque and ‘original’ hits, pre-circa 2015, slowly being overrun, nearly a decade later? Is the sweet-talking Pop Music Machine threatening to flatline the rough and thrilling spikes that made these genres exciting? Dancehall records, compilations, and bootlegs (abundant in decades pre-2010) are becoming increasingly harder to press, alluding to the economics and technology that dictate modern music consumption, and the soundsystem and dubplate culture that birthed it. Today, we have tech behemoths – from Apple Music to Spotify to Youtube – dictating the flow of your next find, overproduced and compressed at 256kbps. Technology, and its influence, from congeneric studio software to AI algorithms, seems to have a levelling effect on the music.

That is an outside-looking-in view, and an unfair representation, a rude generalization, of someone like Masicka – the dancehall deejay from Portman Jamaica who recently signed to Def Jam, and who seems to retain the same mad-max moxie that made him an exciting (and perhaps generational) talent at the time. In a primarily singles-driven genre, his debut album landed to box office triumph at the end of 2021, whilst his grand follow-up album was unveiled in December 2023. Even more so, a slew of singles that both predates the new album, foretells an arc of an artist on the cusp of unlocking a new level, and marrying artistry with that often-elusive thing — reach.

When measured on the metrics of output and influence, the last decade feels bright for dancehall and Jamaica: Breakout stars Shenseea and (grammy-winning) Koffee turned lockdown blues into crossover success (the latter to critical acclaim); genre superstars Sean Paul and Popcaan made compelling album content; industry veterans Spice and Charly Black released their long-awaited debut albums; reggae talents Chronixx, Protoje and Kabaka Pyramid built on their dancehallfooting; smooth operators Kranium and Konshens retained their Midas touch for hit records; amazing vocalists Lila Ike and Jada Kingdom continued their rise; super-producers Rvssian and Dre Skull expanded their reach (the former into pop & reggaeton, the latter into well, everything good and pure); cross-genre and cross-continent hit songs dominated global airwaves; and the weird & wonderful Equiknoxx kept pushing unforeseen boundaries inside the ‘dungeons of dancehall’. All of this, whilst the King remained as prolific as ever, striving to stay dominant from prison (but more on him later).

As the initial spark of ska and rocksteady morphed into reggae music, Jamaica’s flag was firmly established as a music powerhouse in the 1960s. If population was weight, the country was not only punching above its weight-class, but redrawing the boundaries of the ring. “No song, no dub”, yet it could similarly be argued that no other genre has had a wider impact on modern music than dub music, the mutant offspring of reggae. Was it something in the soil? Was it the island’s penchant for adventure? Or its revolutionary spirit? Was it the genius of Lee Scratch Perry and King Tubby? Or all of the above? In the midst of this, dancehall was born, as a counter-movement by (and for) working class inner city Jamaicans who were shut out from ‘uptown’ parties. Dancehall events were new, visceral experiences for its audiences, with low bass frequencies, earthshaking volume and ‘digital’ gyration cranked up to level 11. Even more so, it levelled the field by bringing ‘people’s music’ directly to communities who did not possess radio, and to artists whose music was not played on the radio. There was an invigorating quality to the music, with its gritty and primal depiction of day-to-day subject matter, compared with the more ideological roots & reggae movement.

At the center of this was the physicality of the sound itself, via soundsystems such as Black Scorpio, Silver Hawk and Killimanjaro. Together with the soundsystems, dancehall’s early torchbearers were artists such as Captain Sinbad, Clint Eastwood, Yellowman, Charlie Chaplin, Sister Nany and Lady Saw (and “Sleng Teng” Riddim by King Jammy and Wayne Smith). Yellowman in particular was a fierce proponent of the genre and its ethos, and became one of its first superstars. In the 1990s, the next wave of artists such as Beanie Man, Buju Banton, Mad Cobra, Bounty Killer, Shabba Ranks, Capleton and Elephant Man, who along with a new school of producers such as Dave Kelly, Bobby Digital and Ward 21 sharpened and glistened the riddims with the use of electronic synthesizers and sampling. The arrival of Sean Paul in the early 2000s brought even more mainstream recognition, an international dancehall icon who was able to capsule the fun and immediacy of the genre, whilst being able to retain his songcraft, relevance and longevity in a changing landscape.

Fast forward a decade, when Dre Skull produced Vybz Kartel’s electro-tinged Kingston Story LP in 2010, it potentially marked a pull away from singles into more cohesive long-players. Equally talented Rvssian perhaps signaled the arrival of a pop genius (but one who seems to have surrendered the raw energy of his early work for grander ambition). Since that time, the dancehall hit machine has been chugging along in the last decade, both inspired and uninspired in equal measure, whilst recently being associated with different movements – from (the more colourful) Africa and the UK, to (the more monochrome) trap-dancehall, pop music and ‘tropical house’. Dancehall’s global influence has been unmistakable: from Rihanna and Drake to Jaimie XX and the ‘biggest track on youtube’ (where Justin Bieber characterized the obvious dancehall influence as that of “island music”). You cannot help but think that the heavy lifting done by dancehall over the years to bring its signature syncopated flavour to the orbit of mainstream music, has not received its due flowers. But everything moves in cycles, and the (often valid) fears of expropriation by the West and the (sometimes unfair) overshadowing by a rising Africa aside, dancehall is still alive, kicking. As one astute observer remarks on La Lee’s bracing “Dirt Bounce”, “Dancehall nice again?”

In this cosmopolitan landscape, inspiration on where dancehall could sonically go, is perhaps hinted by a few producers on the frontline of Jamaica’s reggae and R&B scenes: Sean Alaric combines dub pulse with immersive atmospherics on work with Lila Ike, Jesse Royal, and Khxos (and this Burna Boy remix). J.L.L. brings inspired instrumentation and sampling to his work with the emerging talents of Jamaica. Koffee and Jorja Smith producer IzyBeats may have cracked the ultimate slowburner code. A new generation of stunning songstresses are brewing and bubbling just underneath the surface (Shenseea, Jada Kingdom, Lila Ike, Jaz Elise, Naomi Cowan and Sevana are all great vocalists). Natural High Music revive sound-system culture through their ‘future roots’ sound with a rich palette behind the boards. Equiknoxx maybe the most intriguing of them all, over the course of a decade, moving beyond their early dancehall hits to build a planetarium of sound ideas: Their penchant for leftfield instruments and sampling methods has organically expanded their sonic canvas, whilst their growing worldwide network (including some O.G. links), features on heady labels and events and curious side projects have yielded rightful acclaim. In the intro to “Blessed” dancehall legend Buju Banton offers some words of wisdom to Koffee. The hope is that the new school of artists can continue to ignite that brisk and bouncy spark-up, while retaining its Jamaican identity, that make ‘the dance hall’ such an exciting movement.

And one of them, is Masicka. Bursting on to the scene in 2012, Masicka (real name Jauvaon Fearon) hails from Independence City, in Portmore Jamaica. He first rose to prominence through songs that gained traction on local radio stations whilst still in Kalaba High School (“Guh Haad N Done”, “Lose Control” and “Whistling Clean”). His sessions with Equiknoxx (the first of which he secured by winning a DJ competition while in High School) are an interesting body of work, harking back to the salad days where Gavin Blair’s eccentricity brought out something alike in Masicka. The cult-favourite 2012 EP Equiknoxx Music Introduces Masicka to King Tubby is a curious artifact of a brazen young deejay spitting new-school rhymes over timeless dubs, a sign of a things to come at the time. Since that time, he has dabbled in more conventional dancehall, with One Motion Music, Genahsyde (his own imprint) and producers such as Dunw3ll. Fast-forward to 2023, the older-and-wiser Masicka has been on a lethal run of singles.

It’s a run that started around the ‘carbon-rifle rhymes’ of “God Damn”, and continued on with “Drug Lawd”, “Grandfather”, “I wish”, “Pack a Matches”, “King”, “Feisty”, and culminated with the “Tom Brady Freestyle.” The latter contains arguably the most efficient use of Bars since Juelz Santana launched his helicopter-flow, the deadly economy of lines like “Mi gun nuh feel safe wid safety”. Carrying the weight of a timeless sportsman of the modern era, the track does justice to the tag. On the simmering “Update”, Masicka stands back and commands the sonic space over an earthmover bassline, while letting out barks and squeals that momentarily push his voice into 3-octave territory (ha). The track is a powerplay in spatial dynamics, a nod to heavy-duty dub as much as dancehall (“Spend a couple dubplate, make the club shake”), its shoutouts still ringing in the ear after the music ends.

The non-dancehall heads may have discovered Vybz Kartel, widely regarded as the greatest dancehall artist of the modern era, on the eponymous “Diplo Riddim” (from Diplo’s Hollertronix-era debut ‘Florida’ of 2005). This was around the time of JMT, before “Romping Shop” and “Yuh Love” took the world by storm. What makes Vybz so great? It was even on display then: Bluster, street knowledge and charisma all curled into one injection-flow, that was able to navigate any tricky nook of a topic, in that commanding yet gregarious voice you intuitively gravitated towards (Note: Vybz has a great storytelling tone). An artist whose influence runs deep in Jamaica, Kartel’s scope was manifold – a lyricists who was able to do it all with an alluring swagger. And a songwriter who was so quick on the draw, that he has redefined the term ‘prolific’. Even after his conviction for murder in 2014, he continued to release music at a head-spinning rate. And through his label Portmore Empire, the MC also took under his wing emerging talents in the island, including notably Tommy Lee Sparta and Popcaan.

But if Vybz was the Di Teacher and Popcaan was the protege, the latter seems to have graduated from the streets and landed on pastures foreign, his sights set on a wider, more pacific world, rubbing shoulders with a global assembly of stars in the process. Maybe Popcaan was the joyous messiah dancehall needed, on a scenic bridge that crossed over to the town square – but one that still feels authentic, spiritually grounded and expansive. “Something about his voice…pulls you in, draws you in”, says Dre Skull. The Fixtape (the mixtape on soundcloud that accompanied the album proper) may just well be the dancehall statement of the new decade, an exuberant carnival on full-blast, that blurs the lines between a myriad of influences and serves up everything good and wholesome (note: watch an amusing piano-laden Vybz intro segue into a hair-raising cover of Nas’s “Hate Me Now”) In the end, you cannot help but feel the trajectory of Popcaan’s burgeoning career is decidedly less Badman – and more Poppy – than Vybz’s. And perhaps, all the better for it.

So where does that leave us? Even with an opaque incarceration spanning over 12 years, the question of ‘who is the Next Vybz’ is seldom speculated in dancehall circles, often ending rather bluntly (“there is no next Vybz” – and never will be). But on the scale of the gritty streetwise blueprint of Kartel’s best work, there is also Alkaline, and there is Skillbeng, trying to map out designs of their own. Alkaline started out frighteningly-well, but appears to have lost some focus along the way. Skillbeng, who potentially got the nod from Vybz himself, is the more obvious (and direct) comparison, with his piercing delivery, husky circles-around-you flow, and innate starpower. All three appear to possess something singular and special. With a sophomore LP that just landed, Masicka ‘Top ah di game/Tom Brady’ may just be on the inside lane. But can they regulate the paperchase, take calculated risks, and remain fierce? Either way, it’s bound to be intriguing viewing, for both Jamaica and the world.

925 Dancehall Special [Mixtape]

1. Vybz Kartel – Hey Addi [2016]

2. Vybz Kartel – Enemy Zone [2016]

3. Konshens – Purple Touch [2021]

4. Popcaan – Fresh Polo (Ft. Stylo G & Dane Ray) [2020]

5. Vybz Kartel – Loodi (Ft. Shenseea) [2017]

6. Sean Paul – Boom [2021]

7. Konshens – Bassline [2018]

8. Intence – Nuh Behaviour [2022]

9. Spice – Crop Top [2022]

10. Mavado – Bad Girl [2022]

11. Masicka – God Damn [2020]

12. Capleton & Black Brown – Wey Up Deh [2015]

13. Konshens – Gun Head [2021]

14. Popcaan – Bad Yuh Bad [2017]

15. Skillibeng – Prolific [2021]

16. Aidonia & Govana – Earthquake [2023]

17. Koffee & Govana – Rapture (Remix) [2019]

18. Alkaline – Twerc [2021]

19. Stefflon Don – Hurtin’ Me (Ft. Sean Paul, Popcaan & Sizzla) [2018]

20. Laa Lee – Dirt Bounce [2021]

21. Laa Lee – Tip Inna it [2020]

22. Masicka – Update [2021]

23. IWaata – Anyweh [2021]

24. Skillibeng – Stefflon Don (Ft. Stefflon Don) [2021]

25. Kranium - Life of the Party [2021]

26. Jada Kingdom – Fling it Back [2022]

27. Equiknoxx – Uggh (Ft Joey B) [2021]

By: DJ Infrastructur

December 2023

Close-Encounters with DJ Sotofett

The story of the shadowy but towering figure of DJ Sotofett seems to be a long and protracted one. Along with his brother DJ Fett Burger, Sotofett founded Sex Tags Mania, under whose umbrella many-a sound and vision spawned, from extended ambient excursions to rolling reggae riddims to knotty get-down house jams.

Ahead of his Sri Lanka debut at 925 Colombo, instead of giving you this full story, we give you the next best thing—handpicking some our favourite tracks of this incredibly prolific, creative artist:

Jesse – Pohja (DJ Sotofett Mix) [Wania] (2017)

Kicking things off is a Sotofett take (on a track of the Finnish electro act) that feels central and fundamental to his work. Rooted, skeletal, seemingly chugging along to the pulse of earth itself. 7 minutes of Rhythm & Sound-heavy equilibrium, that perfect dancefloor warmer-up. The dreamy B-side here lands on the different end of that spectrum, but arrests, equally.

DJ Sotofett Feat. Haugen Inna Di Bu – Dub Off [Honest Jon’s] (2018)

What seems the start of a new and energized run on Honest Jon’s Records (that included C'Est L'Aventure and Hebi/Haru), “Dub Off” is modern dub done right, with each component – instrumental clarity, weight, space and velocity all measured and delivered to a tee, its keys bright and clamouring. “Dub On” is a more menacing mix while “Dub on Dub” stretches Sotofett’s pads further in to the mystical lands.

DJ Sotofett Meets Abu Sayah – Houran (DJ Sotofett’s Percussion Mix) [Fit Sound] (2015)

I first heard “Houran” at the 2015 rendition of the magical Inner Varnika, when Sex Tags brothers began their festival-closing set. The hypnotic drone (of the yarghol, a middle-eastern instrument, and the harmony vocals) seemed to straddle on for what felt like eternity, yet the percussive elements discreetly building underneath it hinted at what was to come – some magnificent sway – and by the time the bassline and the fuzzed-out kickdrums land, you found yourself completely overpowered.

SW – Reminder (Burridim Mix by DJ Sotofett) [Sued] (2013)

SW’s “Reminder” is a modern classic—a timeless, aquatic Detroit-dreamride that sits atop the spectacular Sued catalogue. Sotofett comes along and turns the tables on its squelchy melancholy, with a junglist bass-heavy ‘burridm’ that clamours and jolts (and spinbacks), all before gorgeous pads usher in a whole new era of feeling.

DJ Sotofett – Current 82 (12 Mix) [Keys of Life] (2016)

Released on Helsinki’s Keys of Life (operating under Säkhö), “Current 82” is an ethereal burner that gradually drifts itself into sensory range, dusts off its keys, to weave out a story that remains with you long after the morning hours of the party. A Sotofett classic.

LNS & DJ Sotofett – Reform [Tresor] (2023)

With frequent collaborator LNS, DJ Sotofett seems to have found a new home in Tresor, with the 2021 LP Sputters landing to critical acclaim. Their most recent collaboration The Reformer EP somewhat moves away from that sound, but retains the attitude. “Reform” contains a vintage Autechre-ian melody envelope that you find in early/mid AFX-era works, while synth tones bob and weave around to form an electro-funk tapestry.

DJ Sotofett Presents Bhakti Crew – Sunrise Mix [Wania] (2012)

One of those perennially in-demand records from his early catalogue, “Sunrise Mix” is that 7am chugger that is missing from your bag, yet “beyond good and evil, there is a field. Let us lie down in that grass.”

DJ Sotofett Feat. Madteo – There’s Gotta be a Way (Vision of Love Club Mix) [Wania] (2013)

DJ Sotofett joins hands with fellow punk Madteo (from NYC), in what is largely now considered an underground classic, Madteo’s robocopped vocals landing all the way from 2199, combined with deluxe pads and a tribal-rollover rhythm.

DJ Sotofett meets Kavadi - Kandhan Karunai [Tresor] (2023)

What is this sorcery? Sotofett collaborates with Tamil artist Kavadi on Tresor’s latest compilation, and it’s a high-octane latenight fever dream.

DJ Sotofett & Gilb’R – Dripping for 97 Mix [Honest Jons] (2015)

Ending with a staple from his debut LP “Drippin' For A Tripp”, a collaboration with Finnish musician Jaakko Eino Kalevi, who’s exquisite carouseling guitar work and Sotofett’s oh-so-subtle drum and synth programming combine to ruffle all the right feathers.

See you on April 29!

“Being in opposition is prime goods in underground culture and the second you are not in opposition anymore you're a performer, not an artist. Know the difference!” – DJ Sotofett

By: DJ Infrastructur

April 2023

Ahead of his Sri Lanka debut at 925 Colombo, instead of giving you this full story, we give you the next best thing—handpicking some our favourite tracks of this incredibly prolific, creative artist:

Jesse – Pohja (DJ Sotofett Mix) [Wania] (2017)

Kicking things off is a Sotofett take (on a track of the Finnish electro act) that feels central and fundamental to his work. Rooted, skeletal, seemingly chugging along to the pulse of earth itself. 7 minutes of Rhythm & Sound-heavy equilibrium, that perfect dancefloor warmer-up. The dreamy B-side here lands on the different end of that spectrum, but arrests, equally.

DJ Sotofett Feat. Haugen Inna Di Bu – Dub Off [Honest Jon’s] (2018)

What seems the start of a new and energized run on Honest Jon’s Records (that included C'Est L'Aventure and Hebi/Haru), “Dub Off” is modern dub done right, with each component – instrumental clarity, weight, space and velocity all measured and delivered to a tee, its keys bright and clamouring. “Dub On” is a more menacing mix while “Dub on Dub” stretches Sotofett’s pads further in to the mystical lands.

DJ Sotofett Meets Abu Sayah – Houran (DJ Sotofett’s Percussion Mix) [Fit Sound] (2015)

I first heard “Houran” at the 2015 rendition of the magical Inner Varnika, when Sex Tags brothers began their festival-closing set. The hypnotic drone (of the yarghol, a middle-eastern instrument, and the harmony vocals) seemed to straddle on for what felt like eternity, yet the percussive elements discreetly building underneath it hinted at what was to come – some magnificent sway – and by the time the bassline and the fuzzed-out kickdrums land, you found yourself completely overpowered.

SW – Reminder (Burridim Mix by DJ Sotofett) [Sued] (2013)

SW’s “Reminder” is a modern classic—a timeless, aquatic Detroit-dreamride that sits atop the spectacular Sued catalogue. Sotofett comes along and turns the tables on its squelchy melancholy, with a junglist bass-heavy ‘burridm’ that clamours and jolts (and spinbacks), all before gorgeous pads usher in a whole new era of feeling.

DJ Sotofett – Current 82 (12 Mix) [Keys of Life] (2016)

Released on Helsinki’s Keys of Life (operating under Säkhö), “Current 82” is an ethereal burner that gradually drifts itself into sensory range, dusts off its keys, to weave out a story that remains with you long after the morning hours of the party. A Sotofett classic.

LNS & DJ Sotofett – Reform [Tresor] (2023)

With frequent collaborator LNS, DJ Sotofett seems to have found a new home in Tresor, with the 2021 LP Sputters landing to critical acclaim. Their most recent collaboration The Reformer EP somewhat moves away from that sound, but retains the attitude. “Reform” contains a vintage Autechre-ian melody envelope that you find in early/mid AFX-era works, while synth tones bob and weave around to form an electro-funk tapestry.

DJ Sotofett Presents Bhakti Crew – Sunrise Mix [Wania] (2012)

One of those perennially in-demand records from his early catalogue, “Sunrise Mix” is that 7am chugger that is missing from your bag, yet “beyond good and evil, there is a field. Let us lie down in that grass.”

DJ Sotofett Feat. Madteo – There’s Gotta be a Way (Vision of Love Club Mix) [Wania] (2013)

DJ Sotofett joins hands with fellow punk Madteo (from NYC), in what is largely now considered an underground classic, Madteo’s robocopped vocals landing all the way from 2199, combined with deluxe pads and a tribal-rollover rhythm.

DJ Sotofett meets Kavadi - Kandhan Karunai [Tresor] (2023)

What is this sorcery? Sotofett collaborates with Tamil artist Kavadi on Tresor’s latest compilation, and it’s a high-octane latenight fever dream.

DJ Sotofett & Gilb’R – Dripping for 97 Mix [Honest Jons] (2015)

Ending with a staple from his debut LP “Drippin' For A Tripp”, a collaboration with Finnish musician Jaakko Eino Kalevi, who’s exquisite carouseling guitar work and Sotofett’s oh-so-subtle drum and synth programming combine to ruffle all the right feathers.

See you on April 29!

“Being in opposition is prime goods in underground culture and the second you are not in opposition anymore you're a performer, not an artist. Know the difference!” – DJ Sotofett

By: DJ Infrastructur

April 2023

Street Soul Soothers

In an era when newly-accessible music technology breathed fresh life and potential into independent musicians, Street Soul – a fusion of various styles of music of black origin – emerged from the bedroom studios, pirate radio stations, blues dances and clubs of late 1980s Britain.

With roots in sound system culture as much as funk and R&B, its architects drew from a musical melting pot. Lovers rock riffs and ethereal synths combined with hip hop breaks. Dub and soul linked up in a dancehall skank. Harmonies levitated above boogie basslines and the unmistakable touch of the 808.

Though it had a hybrid blueprint, the music was stripped-back and raw, made with an uncompromising attitude, DIY energy, and with an ear firmly to the streets and away from the charts. One of the style’s pioneers Toyin Agbetu referred to this in a 2020 interview: “Our tracks were protests against excess, our independence a cry for self-determination.”

Here are five scene-defining favourites:

Sam – Life (Club Mix) [1991]

With roots in sound system culture as much as funk and R&B, its architects drew from a musical melting pot. Lovers rock riffs and ethereal synths combined with hip hop breaks. Dub and soul linked up in a dancehall skank. Harmonies levitated above boogie basslines and the unmistakable touch of the 808.

Though it had a hybrid blueprint, the music was stripped-back and raw, made with an uncompromising attitude, DIY energy, and with an ear firmly to the streets and away from the charts. One of the style’s pioneers Toyin Agbetu referred to this in a 2020 interview: “Our tracks were protests against excess, our independence a cry for self-determination.”

Here are five scene-defining favourites:

Sam – Life (Club Mix) [1991]

A reflective cut about riding out the stresses of life, laced with keys that flicker like passing feelings and blissed-out strings to guide the way.

Bassline - You’ve Gone [1989]

Bassline - You’ve Gone [1989]

A heartbreak anthem with a soul stirring soundscape, soaring vocals and a break that cuts as deep as those breakup scars.

(Reissued on Isle of Jura, 2021)

Mary Pearce - Legacy [199?]

(Reissued on Isle of Jura, 2021)

Mary Pearce - Legacy [199?]

Produced by Agbetu, a sparse tune about hope in a fucked up world, with lush chords, delicate synth licks and the style’s distinctive swing.

Gold In The Shade - Shining Through [1990]

Gold In The Shade - Shining Through [1990]

A love & devotion song with mellow percussion, slick composition and a bassline ripe for the shubeen.

(Reissued on Heels & Souls, 2023)

Ashaye - Dreaming (Jungle Mix) [1994]

(Reissued on Heels & Souls, 2023)

Ashaye - Dreaming (Jungle Mix) [1994]

Jungle in a Street Soul palette: sweet rave dreams, just close your eyes and pour one out for the champagne crew.

(Reissued on V4 Visions, 2021)

By: Max Self

March 2023

(Reissued on V4 Visions, 2021)

By: Max Self

March 2023

Presence & Influence:

Gratitude for the Afro-Sri Lankan musical legacy

The pearl of the Indian ocean has been brewing in its primordial waters: known to ancient Egyptian and Greek worlds, source of all their cinnamon, the shadowy island home of the vilified genius Ravana from the Indian epic Ramayana. Its geography and biodiversity have made it a vortex of trade, travel, pilgrimage and empire. These cultural, biotic and abiotic aspects have acted as selective pressures influencing the cultural destiny of the island and shaping the expression, hopes and habits of its ethnically diverse population.

Sri Lanka’s musical culture has been fruitful and diverse, subject to a variety of influences over the centuries and serving multiple functions from astrological and occult ritual music to harvest song and drinking ballads.

Sri Lanka's proximity to India has led to the adoption of many Indian musical traditions, such as classical Indian instruments and vocal styles. Additionally, the island's strategic coastal location has facilitated the spread of maritime trade, and this has also contributed to the exchange of musical ideas and traditions with other regions.

The country has a long history of colonization, first by the Portuguese in the 16th century, followed by the Dutch in the 17th century, and finally by the British in the 19th century. It has had a significant yet ambivalent impact on the country's musical milieu, as European traditions and instruments were introduced and integrated into the local musical styles.

A relatively unacknowledged but palpable presence in the contemporary popular music of Sri Lanka is its African influence via its small native demographic of Afro-Sri Lankans. These communities have their own unique musical traditions, which have been influenced by both African, European and Sri Lankan musical styles. Today, there are several small communities of African-descended people living in Sri Lanka, the largest of whom refer to themselves as Kaffirs also known as the Sri Lankan Kaffirs.

Although the presence of Africans in Sri Lanka has been documented as far back as the 6th century, when Ethiopian traders were known to have stopped by the island, the origins of the Kaffirs in Sri Lanka can be traced back to the 16th century, when the Portuguese began importing Africans to the island to work on Portuguese-owned plantations as slaves. Many of these people were brought from Portuguese colonies in East Africa, such as Mozambique and Tanzania.

The Sri Lankan Kaffirs are very similar to the Zanj-descended populations in Iraq and Kuwait, and are known in Pakistan as Sheedis and in India as Siddis. They spoke a distinctive Creole based on Portuguese, which evolved to the almost extinct Sri Lankan Kaffir language.

During the Dutch and British colonial periods, the Kaffirs continued to be brought to Sri Lanka as slaves, but they were also used as soldiers to fight against Sinhala Kings and sailors in the Dutch and British armies. In addition, some Kaffirs were brought to the island as part of the British East India Company's labor force.

When Dutch colonialists arrived around 1650, the Kaffirs worked on cinnamon plantations along the southern coast whilst some had settled in the Kandyan kingdom. Some research suggests that Kaffirs were employed as soldiers to fight against Sri Lankan kings, most likely in the Sinhalese-Portuguese War. Having been domiciled in Sri Lanka earlier, the Kaffirs are distinct from the Portuguese Burghers (Sri Lankans with partial Portuguese ancestry). But the Kaffir and the Burghers in the north-east do share language and culture and there has been exchange / intermingling between the communities, albeit poorly documented.

Present day Kaffirs have been assimilated across the country, intermarrying with the local Tamil and Sinhalese population, and three distinct communities in Trincomalee, Negombo and Puttalam still remain. The majority of around 200 families live in the village of Sirambiayadiya, Puttalam.

While the presence of Afro-Sri Lankans is not well documented and has been perceived as marginal, the cultural impact they have had in the island especially via music is marked and undeniable.

Some of the key features of Afro-Sri Lankan music are distinctly African in its use of polyrhythms, call and response and vocal harmonies. Using these techniques to create intricate rhythms and a lively and interactive atmosphere, the singers would often improvise melodies and lyrics, creating a unique and spontaneous sound.

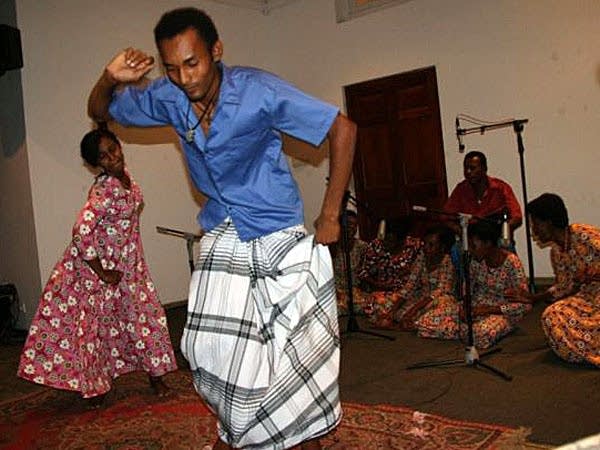

The presence of Afro-Sri Lankan culture in the country’s contemporary music scene is primarily felt through the lasting influence of the Kaffrinha (Kaffir + ‘nha’ (which is the Portuguese diminutive)) which is associated with the Kaffirs and the Portuguese; it is sometimes called Kaffrinha Baila (the Portuguese word for dance), suggesting that the music was a Portuguese take on African music played on the island. Kaffrinha in contemporary Sri Lanka is not simply an Afro-Portuguese blend. It is the fusion of three cultures: African, Portuguese and Sinhalese.

The music is played with percussion and string instruments: violins, mandolins, banjos and guitars. It’s always in 6/8 time, with a very syncopated, three-against-two beat, another suggestion of its roots in African music. Notably apart from the Sinhala language, it seems to be lacking in explicit traits from South Asia: the harmonies and melodies tend to be based around the Western major scale.

The writer R. L. Brohier described the music in a Puttalam village called Sellan Kandel, as Kaffrinha and Chikothi. He wrote in the 20th century that the ‘Kaffir-Portuguese Chikothi’ music had been absorbed into Sri Lankan popular culture, surfacing at gatherings which sought an outlet for hilarity – these were given the heterogeneous term Baila. Although in more recent times, Kaffrinha is often associated with the Portuguese Burgher communities, who continue to live on the coasts of the island.

The kaffrinha song, “Meegalu Maalu'' by the Sri Lankans, was recorded in 1978, so it’s probably not what the music would have sounded like in the 1800s, but it gives us at least a vague approximation.

Kaffrinha is also associated with ‘chorus baila’ (most often simply referred to as Baila), a genre of music that blossomed in postcoloniality. The fountainhead of chorus baila, Mervin Ollington Bastianz, was inspired by kaffrinha and ‘vaada’ baila (debate songs or challenge songs were a popular form of entertainment in Sri Lanka, similar to ‘canto ao desafio in Portugal and Brazil) of which he was the superstar. Unsurprisingly, the rhythms associated with African music were thereby absorbed into chorus baila, perhaps the most cherished form of pop music in the country.

![]()

The simplicity of Bastianz’s narratives and the realities that he addressed, sizzling and simmering over catchy and memorable rhythms, popularized Bailas. Bastianz was a brilliant lyricist, educator and critic. He resonated with the sentiments of a nation whose values were distorted and strained by 450 years of western domination through colonization.

Gerald Wickremasooriya of Sooriya Records phase-shifted Chorus Baila into the age of rock ‘n’ roll with electric guitars, drum kits and synthesizers. Since Bastiansz, Baila has evolved through different styles sung by soloists/groups and travelled overseas with the Sri Lankan diaspora. The dynamics of Baila has reinforced its popularity as the changing tastes of generations fluctuate and unfold. As Sri Lanka discovered and explored her post-independent identity, Baila became more enmeshed in the matrices of her indigenous cultures.

![]()

Chorus Baila is neither an import from Portugal nor a genre that was introduced by the Portuguese. Chorus Baila compositions were influenced by the Afro-Portuguese genre Kaffrinha and Vāda Baila. Chorus Baila signifies a new post-colonial identity, resonant with the recently independent nation of Sri Lanka. Bastianz felt the feelings of the people and voiced their sense, struggle and desires through his compositions of Chorus Baila.

The African contribution to the Sri Lankan culturescape and social life is very much alive in its music and dance genres. Afro-European links of Kaffrinha and Baila are rekindling an interest in the music of Sri Lankans with African and European ancestry. Whilst the various contexts of the kaffrinha remain to be explored through further research, the African roots of kaffrinha is clear.

Although the music of the largest surviving Afro-Sri Lankan community on the island is presently in Sirambiyadiya (Puttalam), it is not Kaffrinha (although often it is mistaken to be), but Manha. Lyrics of Manhas are mostly in Sri Lanka-Portuguese creole, the melodies are distinct from the Batticaloa Cantigas (songs) and Kaffrinhas. While the Creole that they once spoke is almost extinct, it is still the primary language used to transmit their oral histories through music.

The Sirambiyadiya Kaffir’s chant-like songs, known as Manhas, are probably the most traditional of Kaffir music, and has experienced a revival of public interest in recent times. It is polyrhythmic with very few lyrics, passed down orally by their ancestors. It usually has 7 or less lines, repeated over and over again over percussive instruments, “we sing songs about love, the sea, animals, birds and devotional songs.”

They play a pink three-stringed long-necked wooden mandolin with a trapeziform resonator, drums, and found-object instruments: a glass bottle with a metal spoon, two coconut halves and a wooden stool or a metal vessel with two wooden sticks. It is usually played with a 12-piece band and sung in the original Sri Lankan Portuguese Creole.

The songs can sometimes last up to an hour, starting with a downtempo chant, gradually crescendoing into an ecstatic fervor of drumming, singing, clapping. The Sirambiyadiya community’s identity is entwined in their manha performance. Manhas are living testaments of the African diaspora in Sri Lanka and to the historical African presence on the Island.

Today, the Afro-Sri Lankan influence can still be heard in modern Sri Lankan music. Their unique blend of African and Portuguese elements has inspired many contemporary musicians, like Nimal Mendis (particularly in his use of polyrhythms and call and response), and Clarence Wijerwardena (in his approach to vocal harmonies and improvisation). The Afro-Sri Lankan contribution to the island's cultural milieu needs to be recognized, celebrated and preserved. The various nascent music scenes bubbling up in the island need to engage with our Afro-Sri Lankan musical heritage and communities in fresh and engaging ways, perhaps in ways similar to the jazz and classical Hindustani drummer Sarathy Korwar and his engagement with the music and peoples of the Siddi communities in India (producing a stellar album for Ninja Tune, while highlighting the plight of these communities in the cultural conversation). Perhaps now the internet will also sway the trajectories of musical evolution in Sri Lanka to broadcast, sprinkle and reap this heritage in even more unpredictable, yet equally exciting ways.

Listen:http://www.infolanka.com/miyuru_gee/albums/kaffir/

The information for the article above has been primarily sourced from the precious work done by Dr. Shihan de Silva Jayasuriya on Afro Sri Lankan communities and history.

By: Benny Lau

February 2023

Sri Lanka’s musical culture has been fruitful and diverse, subject to a variety of influences over the centuries and serving multiple functions from astrological and occult ritual music to harvest song and drinking ballads.

Sri Lanka's proximity to India has led to the adoption of many Indian musical traditions, such as classical Indian instruments and vocal styles. Additionally, the island's strategic coastal location has facilitated the spread of maritime trade, and this has also contributed to the exchange of musical ideas and traditions with other regions.

The country has a long history of colonization, first by the Portuguese in the 16th century, followed by the Dutch in the 17th century, and finally by the British in the 19th century. It has had a significant yet ambivalent impact on the country's musical milieu, as European traditions and instruments were introduced and integrated into the local musical styles.

A relatively unacknowledged but palpable presence in the contemporary popular music of Sri Lanka is its African influence via its small native demographic of Afro-Sri Lankans. These communities have their own unique musical traditions, which have been influenced by both African, European and Sri Lankan musical styles. Today, there are several small communities of African-descended people living in Sri Lanka, the largest of whom refer to themselves as Kaffirs also known as the Sri Lankan Kaffirs.

Presence

Although the presence of Africans in Sri Lanka has been documented as far back as the 6th century, when Ethiopian traders were known to have stopped by the island, the origins of the Kaffirs in Sri Lanka can be traced back to the 16th century, when the Portuguese began importing Africans to the island to work on Portuguese-owned plantations as slaves. Many of these people were brought from Portuguese colonies in East Africa, such as Mozambique and Tanzania.

The Sri Lankan Kaffirs are very similar to the Zanj-descended populations in Iraq and Kuwait, and are known in Pakistan as Sheedis and in India as Siddis. They spoke a distinctive Creole based on Portuguese, which evolved to the almost extinct Sri Lankan Kaffir language.