In our latest, we take a look at Masicka and modern dancehall, as the young artist from Portmore Jamaica continues his godly run. Is he the heir to Vybz Kartel’s throne? Time to find out.

Sometimes it feels like the globalization of dancehall and afrobeats (and convergence of genres in general) is making everything sound monolithic. Is the maverick spirit that characterized some of the more rhythmically fierce, risque and ‘original’ hits, pre-circa 2015, slowly being overrun, nearly a decade later? Is the sweet-talking Pop Music Machine threatening to flatline the rough and thrilling spikes that made these genres exciting? Dancehall records, compilations, and bootlegs (abundant in decades pre-2010) are becoming increasingly harder to press, alluding to the economics and technology that dictate modern music consumption, and the soundsystem and dubplate culture that birthed it. Today, we have tech behemoths – from Apple Music to Spotify to Youtube – dictating the flow of your next find, overproduced and compressed at 256kbps. Technology, and its influence, from congeneric studio software to AI algorithms, seems to have a levelling effect on the music.

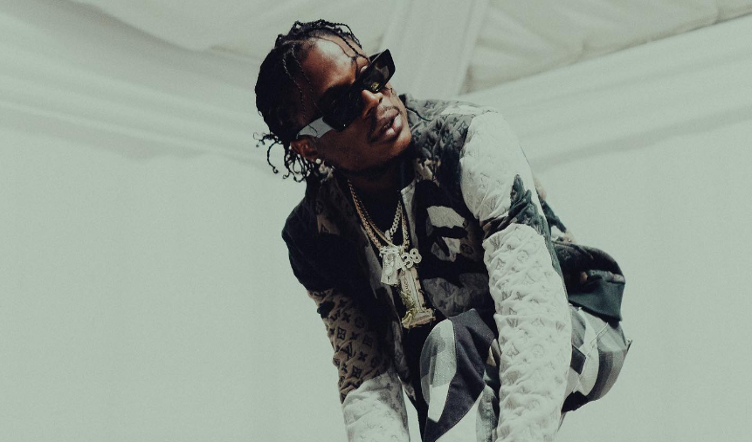

That is an outside-looking-in view, and an unfair representation, a rude generalization, of someone like Masicka – the dancehall deejay from Portman Jamaica who recently signed to Def Jam, and who seems to retain the same mad-max moxie that made him an exciting (and perhaps generational) talent at the time. In a primarily singles-driven genre, his debut album landed to box office triumph at the end of 2021, whilst his grand follow-up album was unveiled in December 2023. Even more so, a slew of singles that both predates the new album, foretells an arc of an artist on the cusp of unlocking a new level, and marrying artistry with that often-elusive thing — reach.

When measured on the metrics of output and influence, the last decade feels bright for dancehall and Jamaica: Breakout stars Shenseea and (grammy-winning) Koffee turned lockdown blues into crossover success (the latter to critical acclaim); genre superstars Sean Paul and Popcaan made compelling album content; industry veterans Spice and Charly Black released their long-awaited debut albums; reggae talents Chronixx, Protoje and Kabaka Pyramid built on their dancehallfooting; smooth operators Kranium and Konshens retained their Midas touch for hit records; amazing vocalists Lila Ike and Jada Kingdom continued their rise; super-producers Rvssian and Dre Skull expanded their reach (the former into pop & reggaeton, the latter into well, everything good and pure); cross-genre and cross-continent hit songs dominated global airwaves; and the weird & wonderful Equiknoxx kept pushing unforeseen boundaries inside the ‘dungeons of dancehall’. All of this, whilst the King remained as prolific as ever, striving to stay dominant from prison (but more on him later).

As the initial spark of ska and rocksteady morphed into reggae music, Jamaica’s flag was firmly established as a music powerhouse in the 1960s. If population was weight, the country was not only punching above its weight-class, but redrawing the boundaries of the ring. “No song, no dub”, yet it could similarly be argued that no other genre has had a wider impact on modern music than dub music, the mutant offspring of reggae. Was it something in the soil? Was it the island’s penchant for adventure? Or its revolutionary spirit? Was it the genius of Lee Scratch Perry and King Tubby? Or all of the above? In the midst of this, dancehall was born, as a counter-movement by (and for) working class inner city Jamaicans who were shut out from ‘uptown’ parties. Dancehall events were new, visceral experiences for its audiences, with low bass frequencies, earthshaking volume and ‘digital’ gyration cranked up to level 11. Even more so, it levelled the field by bringing ‘people’s music’ directly to communities who did not possess radio, and to artists whose music was not played on the radio. There was an invigorating quality to the music, with its gritty and primal depiction of day-to-day subject matter, compared with the more ideological roots & reggae movement.

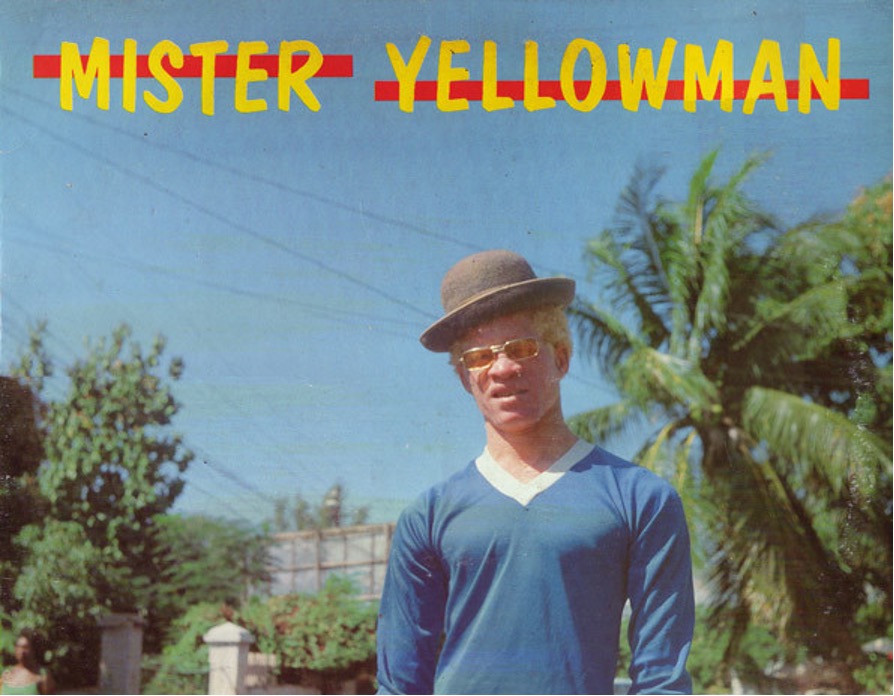

At the center of this was the physicality of the sound itself, via soundsystems such as Black Scorpio, Silver Hawk and Killimanjaro. Together with the soundsystems, dancehall’s early torchbearers were artists such as Captain Sinbad, Clint Eastwood, Yellowman, Charlie Chaplin, Sister Nany and Lady Saw (and “Sleng Teng” Riddim by King Jammy and Wayne Smith). Yellowman in particular was a fierce proponent of the genre and its ethos, and became one of its first superstars. In the 1990s, the next wave of artists such as Beanie Man, Buju Banton, Mad Cobra, Bounty Killer, Shabba Ranks, Capleton and Elephant Man, who along with a new school of producers such as Dave Kelly, Bobby Digital and Ward 21 sharpened and glistened the riddims with the use of electronic synthesizers and sampling. The arrival of Sean Paul in the early 2000s brought even more mainstream recognition, an international dancehall icon who was able to capsule the fun and immediacy of the genre, whilst being able to retain his songcraft, relevance and longevity in a changing landscape.

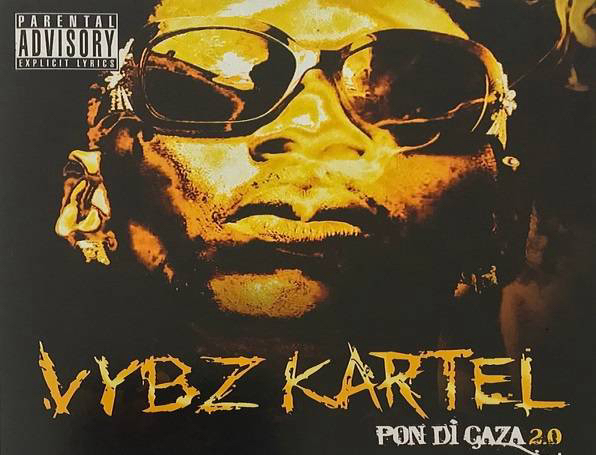

Fast forward a decade, when Dre Skull produced Vybz Kartel’s electro-tinged Kingston Story LP in 2010, it potentially marked a pull away from singles into more cohesive long-players. Equally talented Rvssian perhaps signaled the arrival of a pop genius (but one who seems to have surrendered the raw energy of his early work for grander ambition). Since that time, the dancehall hit machine has been chugging along in the last decade, both inspired and uninspired in equal measure, whilst recently being associated with different movements – from (the more colourful) Africa and the UK, to (the more monochrome) trap-dancehall, pop music and ‘tropical house’. Dancehall’s global influence has been unmistakable: from Rihanna and Drake to Jaimie XX and the ‘biggest track on youtube’ (where Justin Bieber characterized the obvious dancehall influence as that of “island music”). You cannot help but think that the heavy lifting done by dancehall over the years to bring its signature syncopated flavour to the orbit of mainstream music, has not received its due flowers. But everything moves in cycles, and the (often valid) fears of expropriation by the West and the (sometimes unfair) overshadowing by a rising Africa aside, dancehall is still alive, kicking. As one astute observer remarks on La Lee’s bracing “Dirt Bounce”, “Dancehall nice again?”

In this cosmopolitan landscape, inspiration on where dancehall could sonically go, is perhaps hinted by a few producers on the frontline of Jamaica’s reggae and R&B scenes: Sean Alaric combines dub pulse with immersive atmospherics on work with Lila Ike, Jesse Royal, and Khxos (and this Burna Boy remix). J.L.L. brings inspired instrumentation and sampling to his work with the emerging talents of Jamaica. Koffee and Jorja Smith producer IzyBeats may have cracked the ultimate slowburner code. A new generation of stunning songstresses are brewing and bubbling just underneath the surface (Shenseea, Jada Kingdom, Lila Ike, Jaz Elise, Naomi Cowan and Sevana are all great vocalists). Natural High Music revive sound-system culture through their ‘future roots’ sound with a rich palette behind the boards. Equiknoxx maybe the most intriguing of them all, over the course of a decade, moving beyond their early dancehall hits to build a planetarium of sound ideas: Their penchant for leftfield instruments and sampling methods has organically expanded their sonic canvas, whilst their growing worldwide network (including some O.G. links), features on heady labels and events and curious side projects have yielded rightful acclaim. In the intro to “Blessed” dancehall legend Buju Banton offers some words of wisdom to Koffee. The hope is that the new school of artists can continue to ignite that brisk and bouncy spark-up, while retaining its Jamaican identity, that make ‘the dance hall’ such an exciting movement.

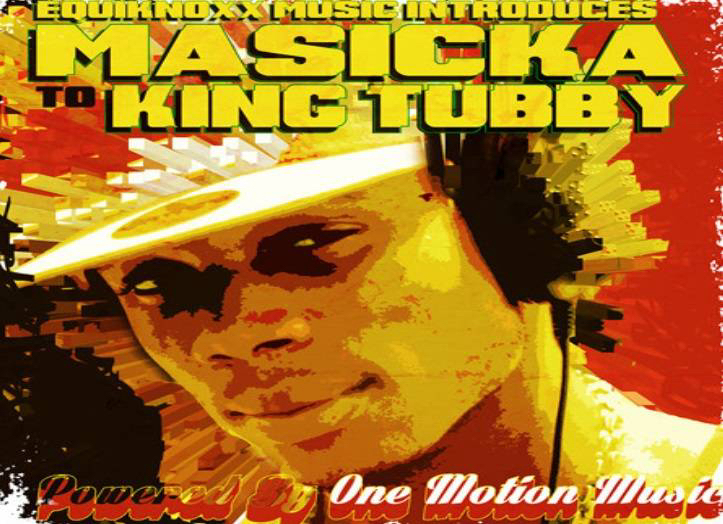

And one of them, is Masicka. Bursting on to the scene in 2012, Masicka (real name Jauvaon Fearon) hails from Independence City, in Portmore Jamaica. He first rose to prominence through songs that gained traction on local radio stations whilst still in Kalaba High School (“Guh Haad N Done”, “Lose Control” and “Whistling Clean”). His sessions with Equiknoxx (the first of which he secured by winning a DJ competition while in High School) are an interesting body of work, harking back to the salad days where Gavin Blair’s eccentricity brought out something alike in Masicka. The cult-favourite 2012 EP Equiknoxx Music Introduces Masicka to King Tubby is a curious artifact of a brazen young deejay spitting new-school rhymes over timeless dubs, a sign of a things to come at the time. Since that time, he has dabbled in more conventional dancehall, with One Motion Music, Genahsyde (his own imprint) and producers such as Dunw3ll. Fast-forward to 2023, the older-and-wiser Masicka has been on a lethal run of singles.

It’s a run that started around the ‘carbon-rifle rhymes’ of “God Damn”, and continued on with “Drug Lawd”, “Grandfather”, “I wish”, “Pack a Matches”, “King”, “Feisty”, and culminated with the “Tom Brady Freestyle.” The latter contains arguably the most efficient use of Bars since Juelz Santana launched his helicopter-flow, the deadly economy of lines like “Mi gun nuh feel safe wid safety”. Carrying the weight of a timeless sportsman of the modern era, the track does justice to the tag. On the simmering “Update”, Masicka stands back and commands the sonic space over an earthmover bassline, while letting out barks and squeals that momentarily push his voice into 3-octave territory (ha). The track is a powerplay in spatial dynamics, a nod to heavy-duty dub as much as dancehall (“Spend a couple dubplate, make the club shake”), its shoutouts still ringing in the ear after the music ends.

The non-dancehall heads may have discovered Vybz Kartel, widely regarded as the greatest dancehall artist of the modern era, on the eponymous “Diplo Riddim” (from Diplo’s Hollertronix-era debut ‘Florida’ of 2005). This was around the time of JMT, before “Romping Shop” and “Yuh Love” took the world by storm. What makes Vybz so great? It was even on display then: Bluster, street knowledge and charisma all curled into one injection-flow, that was able to navigate any tricky nook of a topic, in that commanding yet gregarious voice you intuitively gravitated towards (Note: Vybz has a great storytelling tone). An artist whose influence runs deep in Jamaica, Kartel’s scope was manifold – a lyricists who was able to do it all with an alluring swagger. And a songwriter who was so quick on the draw, that he has redefined the term ‘prolific’. Even after his conviction for murder in 2014, he continued to release music at a head-spinning rate. And through his label Portmore Empire, the MC also took under his wing emerging talents in the island, including notably Tommy Lee Sparta and Popcaan.

But if Vybz was the Di Teacher and Popcaan was the protege, the latter seems to have graduated from the streets and landed on pastures foreign, his sights set on a wider, more pacific world, rubbing shoulders with a global assembly of stars in the process. Maybe Popcaan was the joyous messiah dancehall needed, on a scenic bridge that crossed over to the town square – but one that still feels authentic, spiritually grounded and expansive. “Something about his voice…pulls you in, draws you in”, says Dre Skull. The Fixtape (the mixtape on soundcloud that accompanied the album proper) may just well be the dancehall statement of the new decade, an exuberant carnival on full-blast, that blurs the lines between a myriad of influences and serves up everything good and wholesome (note: watch an amusing piano-laden Vybz intro segue into a hair-raising cover of Nas’s “Hate Me Now”) In the end, you cannot help but feel the trajectory of Popcaan’s burgeoning career is decidedly less Badman – and more Poppy – than Vybz’s. And perhaps, all the better for it.

So where does that leave us? Even with an opaque incarceration spanning over 12 years, the question of ‘who is the Next Vybz’ is seldom speculated in dancehall circles, often ending rather bluntly (“there is no next Vybz” – and never will be). But on the scale of the gritty streetwise blueprint of Kartel’s best work, there is also Alkaline, and there is Skillbeng, trying to map out designs of their own. Alkaline started out frighteningly-well, but appears to have lost some focus along the way. Skillbeng, who potentially got the nod from Vybz himself, is the more obvious (and direct) comparison, with his piercing delivery, husky circles-around-you flow, and innate starpower. All three appear to possess something singular and special. With a sophomore LP that just landed, Masicka ‘Top ah di game/Tom Brady’ may just be on the inside lane. But can they regulate the paperchase, take calculated risks, and remain fierce? Either way, it’s bound to be intriguing viewing, for both Jamaica and the world.

925 Dancehall Special [Mixtape]

1. Vybz Kartel – Hey Addi [2016]

2. Vybz Kartel – Enemy Zone [2016]

3. Konshens – Purple Touch [2021]

4. Popcaan – Fresh Polo (Ft. Stylo G & Dane Ray) [2020]

5. Vybz Kartel – Loodi (Ft. Shenseea) [2017]

6. Sean Paul – Boom [2021]

7. Konshens – Bassline [2018]

8. Intence – Nuh Behaviour [2022]

9. Spice – Crop Top [2022]

10. Mavado – Bad Girl [2022]

11. Masicka – God Damn [2020]

12. Capleton & Black Brown – Wey Up Deh [2015]

13. Konshens – Gun Head [2021]

14. Popcaan – Bad Yuh Bad [2017]

15. Skillibeng – Prolific [2021]

16. Aidonia & Govana – Earthquake [2023]

17. Koffee & Govana – Rapture (Remix) [2019]

18. Alkaline – Twerc [2021]

19. Stefflon Don – Hurtin’ Me (Ft. Sean Paul, Popcaan & Sizzla) [2018]

20. Laa Lee – Dirt Bounce [2021]

21. Laa Lee – Tip Inna it [2020]

22. Masicka – Update [2021]

23. IWaata – Anyweh [2021]

24. Skillibeng – Stefflon Don (Ft. Stefflon Don) [2021]

25. Kranium - Life of the Party [2021]

26. Jada Kingdom – Fling it Back [2022]

27. Equiknoxx – Uggh (Ft Joey B) [2021]

By: DJ Infrastructur

December 2023