ACID. The carboard separator read in big, bold letters. It was a drizzly Tokyo evening, and I was at Technique, the infamous Japanese record store (now defunct). Inside a lowly-priced basement bin, lay a 12” carrying an obscure Tin Man remix. There was a line of record players along the windowsill. I put the needle on the record, not knowing the full story at the time. Mayhem ensued, rain shards coming down on the glass at an incline. As did the (s)tabs of acid – A fascinating name, a fascinating genre, a fascinating device. But what of it?

Tin Man (real name Johannes Auvinen) is one of the best to ever do it on the Roland TB-303, the (posthumously-deemed) genius Japanese bass synthesizer that transformed techno and house music as we know it. Born in California and based in Vienna, Johannes is known for his mastery of all things acid, the subgenre of dance music born out of Chicago and the 303, in early to mid-1980s. In a way, perhaps acid was to dance music what new wave was to rock music, an extension cord that expanded the original blueprint, while managing to crossover to a wider audience in its heyday and power few other exciting subgenres too. The Roland 303 was what made it possible: Combining house and techno music’s four-on-the-floor beats with its signature ‘squelchy’ basslines, acid house birthed a fresh sound for dance music where the focus moved to sonic texture and atmosphere. The unique, undulating sounds were made possible by creating variation in the 303’s bass pattern output, by manipulating its filter resonance, cutoff frequency and octave parameters.

“The most unique sound of the history of the world” is how DJ Pierre describes the 303 (as Acid Tracks would testify). One third of seminal Phuture, (the early adaptors of the 303, along with Charanjit Singh, Alexander Robotnick and Sleezy D), Pierre reveals that their quest to “create a sound that was different” in the early 1980’s ended with their discovery of this Roland synthesizer. Designed by Tadao Kikumoto, Chief Engineer (and Managing Director) of Japan’s Roland Corporation at the time, its original intent was to act as a bass synthesizer that simulated the bass guitar (Tadao was the Chief Designer of the TB-808 and the TB-909 too). The TB-303 was a commercial failure, however, and was discontinued within 3 years of unveiling in 1981. Incredibly, Tadao and his team only heard about the 303’s influence on underground music more than 10 years later, through a “well-informed guy from an overseas department.” Since then, from Orbital to Plastikman and Aphex Twin, from LFO to Daft Punk and Timbaland, the synthesizer has forged a path of its own. “Every twist and turn…never to be heard exactly the same way” DJ Pierre recaps, referencing the inimitability of this almost-chance intersection of machine vs sound.

Acid house’s broader influence cannot be underscored, its ubiquitous tentacles seeping into several future styles of electronic dance music (from jungle to triphop), while at times transcending it to inoculate the orbit of pop music too. Its early purveyors included promoters and artists of Ibiza circa ’87, as well as the Second Summer of Love and ‘Madchester’, which were uninhibited music and rave movements that defined UK’s music scene and club culture for years to come. This passage of time carried the same free-spirited verve and anti-establishment leanings of the hippie movement of 1960s San Francisco, powered by the newfound sound of acid, resonant warehouse settings, charming fashion and the liberal use of MDMA. In the meantime, legendary artists such as Baby Ford, Adonis, Mr Fingers, A Guy Called Gerald, the KLF and 808 State, Aphex Twin and Josh Wink took the acid house sound in further exciting and compelling directions.

Fast-forward 15 years, Tin Man arrived, at a slightly different phase of underground dance music (around the time of microhouse, M_nus mnml and French house) or in fact, independent from it. A precision technician and a refined songwriter, you would think the machine (the Roland 303) would be scope-limiting for Tin Man, but the opposite is true. “It is amorphous and abstract, yet has a narrative quality that transports you”, he says of acid. In the process, Auvinen has not only seized both the genre and the device, but reimagined their (increasingly worn-out) direction at the time, to traverse a world of U-shaped valleys and troughs: Observable but not yet fully explored territories, for both machine and man (with a little help from other gear too, of course).

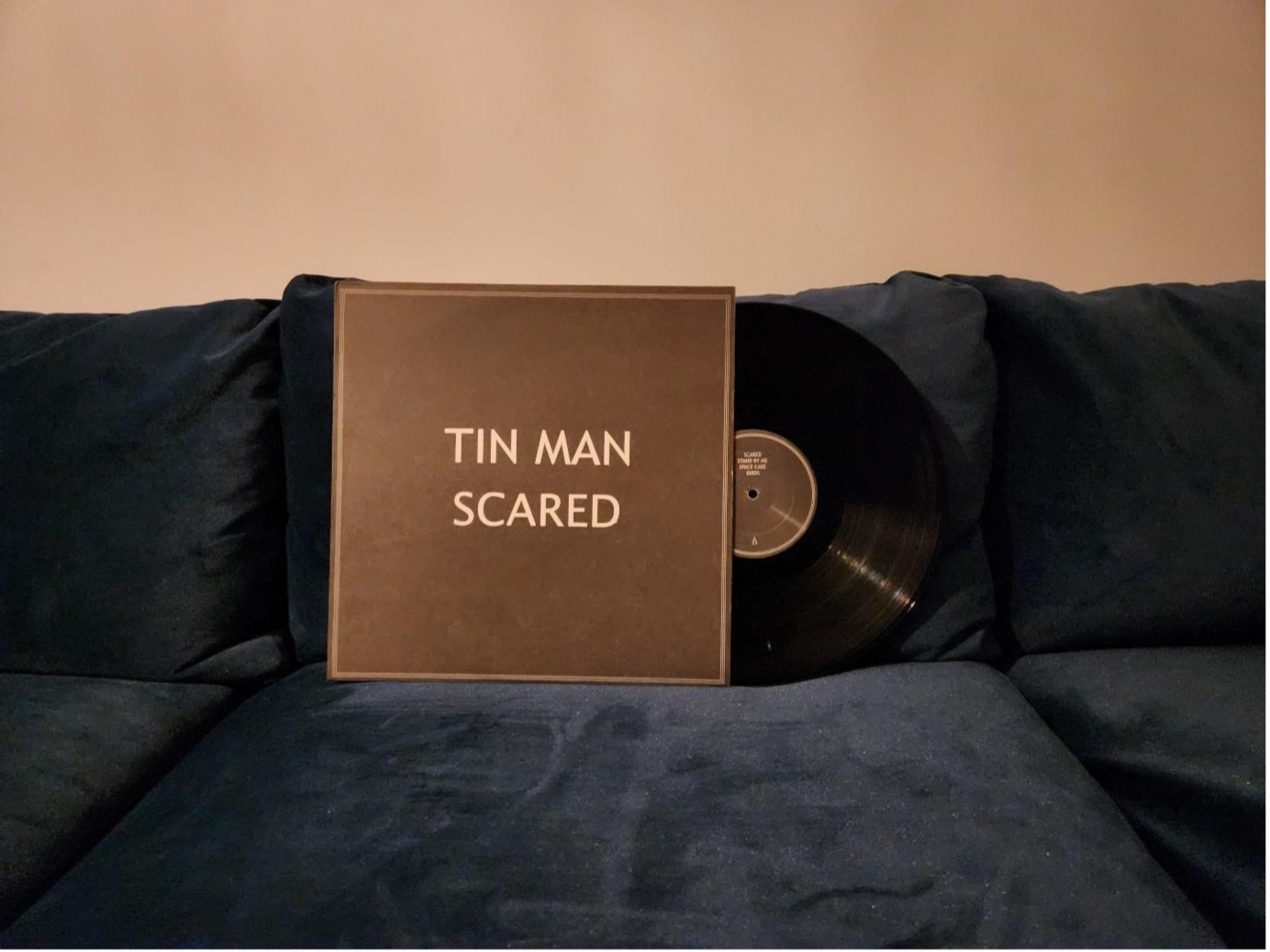

Let’s start with the LPs: Acid Acid (2005) was foundational – barebones analog workouts that marked his arrival. Wasteland’s(2008) drony electronics took things towards an icy Detroit-Chicago nexus. Scared (2010) combined (opinion-dividing) vocals with moving, Ambien-induced drama (and at times, dread). Perfume (2011) was more vivid vox house, jazz-club at worst, radiant at its best. Vienna Blue (2011) reinvented the wheel (again), with a ‘winter album’ of classical strings, chamber music and romance. Vocal-less Neo Neo Acid (2012) felt like a crucial landmark, distilling the Tin Man essence into vintage understated melancholy. Ode (2014) amplified the kickdrums, basslines and ‘dark matter’, marching things towards a dub-techno basement. Dripping Acid (2017) funneled 17 immaculate cuts (of the 12” series) of urgent, pinging, frenzied and at times otherworldly acid techno, with Tin Man in his most relentless, cohesive element. Arles (2023) subdued the acid and channeled the forcefield towards serene, cosmic electronica.

(Continuing this dense rundown), then there were the 12”s (and collaborations): Love Sex Acid (2006) was a lush spiral staircase, Luomo-meets-Mr Fingers. Keys of Life Acid (2006) contained the life-altering “Tip the Acid”, a portal to the 303 afterlife. Acid Test 01 (2011) yielded “Nonneo” and the rarified Donato Dozzy remix. Meanwhile, Tin Man’s shadowy collaborations with artists such as Gunnar Huslam (as Romans), Foreign Material and Cassegrain have explored the uncanny nooks of these soundscapes. Dov’s anthemic Silent Cities (2019) (with Mexico’s Gabo Barranco) and Ociya’s Power of Ten (2020) (with Patricia) were unheralded gems, the latter’s IDM-tinged tracks recorded live with apparently barely any editing. Rolling Ones (2016) (with Jordan Poling) were deep-sided burners, powered by vintage locomotives. Acid Test 11 (2016) (with Josef K and Winter Son) gave “Fates Unknown” and “Pendle By Night”, that capsuled the existential unrest threaded through most of the Tin Man catalogue.

The best things are borrowed. Tin Man seems to hold a shared vision of music than most (“the history is always that everything's taking from other places”), understanding (and even embracing) the cyclic nature of things: He has quietly pushed the envelope of acid, knowing that what is good has always been built on what came before. Beyond songwriting, he seems to be committed to a uniquely spatial sound design – maybe why everything sounds this good, his studio endeavours aiming to model a user experience that confounds. Similarly, ‘meaning’ has hung in the air ambiguously, in both word and melody, in an unusually comforting nexus. There’s an Overman quality to it all, standing alone from the pack, singular in mission: An admittedly committed participant of a (vaporous) underground, yet careful not to be defined by it.

Hidden Acid EP, Released in September 2023, marks Tin Man’s return to 303-centered label Acid Test after 5 long (and lonesome) years. It’s a return to the base, after range-defining outings towards ambient and electronica (and resting his fans fears of selling off his hardware online – as one reassured – maybe it’s just housekeeping?). On Hidden Acid, Tin Man seems to negotiate and wrangle every drip of emotion out of the machines: “Running Acid” is a moody nightbus jaunting around town, its lead synth arpeggio bobbin’ and weavin’ around some (club-destroying) acid-traffic, intensifying by the minute. “Hidden Acid” is part G-funk, AFX and a 90s brickhouse rave – when a doused snare lands two minutes in, you are already busy Trainspotting. The pensive closer “Wrapped Up Acid” laces more Roland spliffs around a chord-choir and shifting drums. The feelings are full-scale but never precious – everything seems to operate within a certain circadian rhythm (as captured by the artwork).

Although he has made great music all throughout his career (despite the limitations originally perceived of his um, field), it felt like the 2011’s Neo Neo and the “Devine Acid” era transcended the borders of acid house, through sinuous melody-stories that permanently infiltrated your subconscious mind, and somehow, hijacked the dancefloor too. “Swaying Acid” seems to be of the same DNA: dazzling congas and 303-voodoo dribbling around glistening platinum pads – pads that everlast, and bleed into new borderlands. Too much acid. Sweeping, sublime acid.

By: Tarifa Banks

January 2024